ART/WORK: How the Government-Funded CETA Jobs Put Artists to Work

For the last two years, curators Jodi Waynberg and Molly Garfinkel have been piecing together the first extensive history of little-known arts employment programs created under the federal Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA), which created jobs for tens of thousands of American cultural workers in the 1970s. Their joint exhibition, ART/WORK: How the Government-Funded CETA Jobs Put Artists to Work, highlighted the creative and political possibilities that CETA provided to New York City artists, many of whom are still working today.

Introduced by Nixon in 1973, the first and last federal program to provide jobs for artists since the Works Progress Administration (WPA) now seems like a relic of a pre-Reagan United States. Artists were compensated as public service workers, as well as producers of individual projects. For that reason, Waynberg and Garfinkel are now working to uncover CETA’s impact across the country, despite the lack of coherent documentation. In the following interview with journalist and organizer Billie Anania, they discussed this process.

Weaving class at P.S. 2 (school-age day care center) led by artist Glenda Stoller, 1978. Photo: Blaise Tobia for the CCF Artists Project Documentation Unit. Blaise Tobia © 2023.

Billie Anania: As someone who writes about art and labor, I was surprised to discover CETA for the first time through your exhibition, which focused on the program administered by the Cultural Council Foundation (CCF) in New York. Where has your research taken you since then?

Jodi Waynberg: We want to find out whether the robustness and shape of the New York model tracks elsewhere, or if other models existed in places like Baltimore, San Francisco, Atlanta, and the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma. Right now, that means combing through CETA applications, local newspapers, and private collections, and interviewing former CETA artists and administrators from around the country, while also figuring out what worked here.

Molly Garfinkel: Unlike the WPA, CETA was not centrally documented in the same way, and the federal government did not hold copyrights for work produced under it. In other words, CETA-related material is everywhere — owned either by artists or community organizations, or by the cities, or by nobody because it no longer exists. There was no central repository for collecting these statistics, so we are really compiling from scratch.

BA: It’s interesting to think about CETA from a political economy perspective, developed under Nixon as all the big labor unions started turning Republican. What were the specific conditions that led to its creation, and how did it aid the cultural industries?

MG: This was a response to rising rates of unemployment and inflation, as well as an attempt to consolidate programs built into the War on Poverty, including workforce development and training. When Nixon launched it, his idea was to decentralize the funds and send them out to states, where it would be applied based on local needs. And again, this was not specifically an arts program, so the federal government was measuring how many jobs were created, how many hours people could work, and how many people could positively transition from CETA to the public or private sector. It was about jobs and training, so as much about process as product.

It’s important to note that the National Endowments for the Arts and Humanities, created in the mid-1960s, were still in their nascence. The public arts infrastructures, including state and local arts councils, were just getting their sea legs. Even in New York, the Department of Cultural Affairs was relatively new, but they became a supportive partner through the involvement of Cheryl McClenney and Henry Geldzahler.

JW: These are all agencies we rely on now. During CETA, the leadership of these agencies became deeply engaged with people on the ground doing the work, participating in conversations and attending conferences. While the CETA funding wasn’t routed through them, they didn’t sit in isolation. They truly got in the mud with one another to understand what was working and how to sustain it.

Also, during the Carter administration, Department of Labor (DoL) Assistant Secretary Ernest Green organized the 1979 conference Putting the Arts to Work, which was meant to encourage states and cities to develop robust CETA arts programming. This was a very unusual role for someone in the DoL to play electively. For instance, in his introductory statement, Green explicitly recognized the economic development value of arts programming.

CETA workers protest cutbacks outside of the Department of Labor in Manhattan. May 23, 1979. Photo: Sarah Wells for the CCF Artist Project Documentation Unit.

BA: That is really thought-provoking given CETA’s death at the outset of Reaganomics, which basically fast-tracked the erosion of labor rights from then to now. But for a brief moment, so much seemed possible. How would you describe its lingering impact today?

JW: CETA was significant in moving the needle away from project-based to skill-based evaluation systems. You were employed as a person with a specific set of skills and expertise that were applicable for both your own interests and those of the larger community. The process of piecing together myriad applications of CETA funds to the arts and engaging with contemporary programs of a similar nature, including the introduction of substantial Universal Basic Income programs across sectors, now allows us to build a more extensive picture of workforce sustainability.

This is not how we often hear the work of artists or cultural workers being described. Certainly, there is a lot of advocacy within the sector, but not in broader workforce conversations. But today, Creatives Rebuild New York (CRNY) draws from this history and presents a clear position that cultural workers are valuable beyond our field.

MG: Of the nearly 500 artists and administrators employed through CETA in New York, most of them stayed within the arts industries for the next 45 to 50 years. Something was clearly working! But there’s still so much to uncover — what this looked like in formerly industrial towns, how this applied to cultural workers who were not artists, and what artists and administrators took with them for the remainder of their careers.

In New York, the CCF project administrators, the Department of Cultural Affairs, and the Department of Employment did so much research leading up to the launch of the local CETA Artists Project. They built city-wide coalitions across artist communities into a robust, thoughtful program structure, much like Creatives Rebuild New York engaged in statewide coalition building to express shared values present in the support of working artists. CRNY also consulted with many of these CETA architects, participants, and beneficiaries, so it’s wonderful to see its legacy continue in this way.

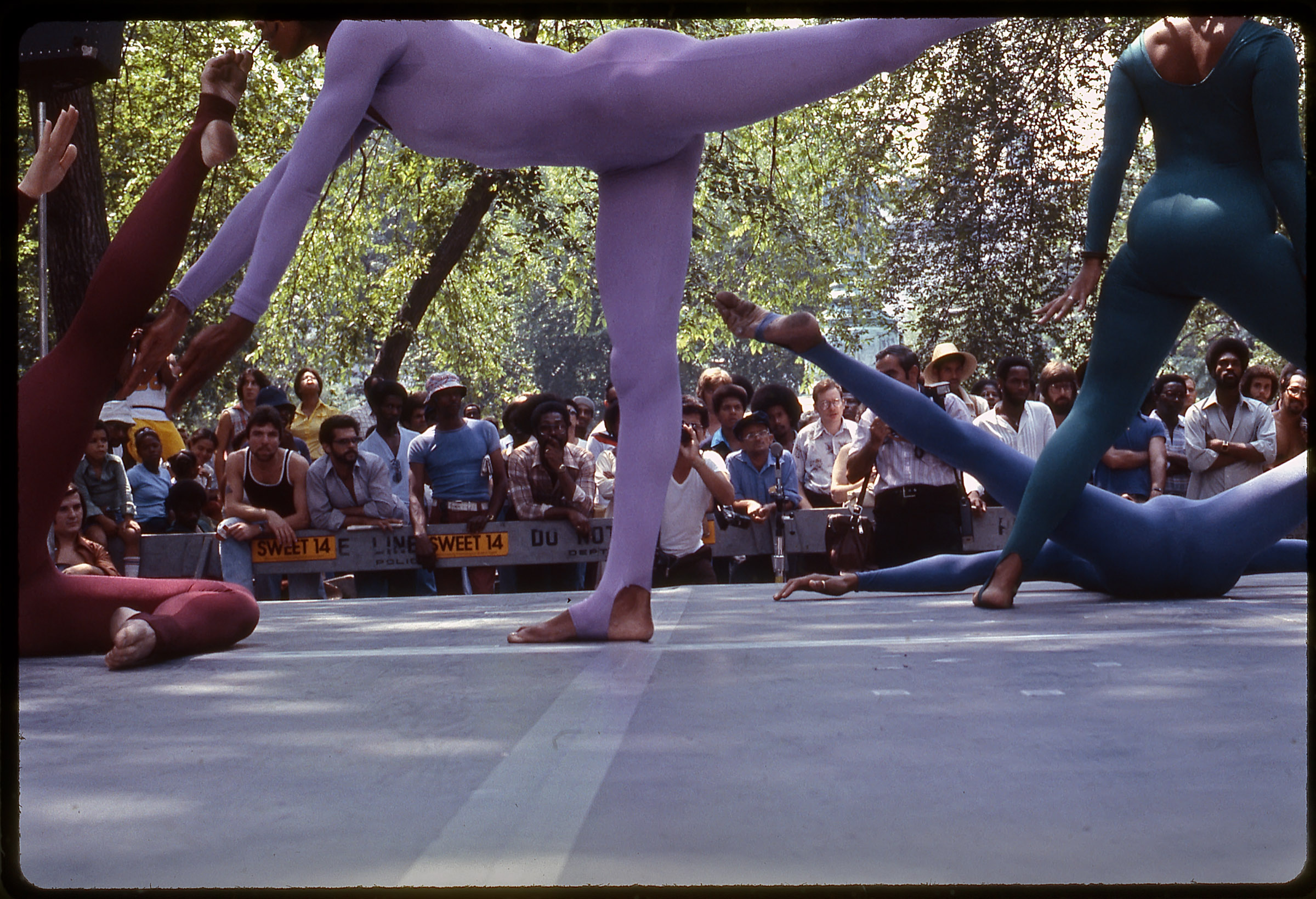

Performance of Ellsworth Ausby’s InnerSpace/OuterSpace at Sweet 14 (Union Square). August 14, 1978. Photo: Blaise Tobia for the CCF Artists Project Documentation Unit. Blaise Tobia © 2023.