Crip Coin: Disability, Public Benefits, and Guaranteed Income

This is the webpage version of this report. You can also access the PDF version.

Contents

Part 3: How to Increase and Protect Access to Public Benefit Programs

Part 1: Introduction

The U.S. movement for guaranteed income (GI) is growing. As more people experience the transformative potential of no-strings-attached cash assistance, we can better understand the limits of existing anti-poverty initiatives and how unrestricted aid can help fill the gaps. One question continues to surface among advocates, organizers, and program administrators: How does cash interact with public benefit programs? This is especially important for disabled people who use means-tested cash assistance, like the federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program, as their primary source of support. People who use public benefits are experts about cash, but they are often left out of the design, implementation, and research about guaranteed income programs.

This report lays out some of the relationships between disability, public benefits, and cash. It offers ideas for future movement work that harnesses the critical insights of disability organizing. We draw on lessons from the Creatives Rebuild New York (CRNY) Guaranteed Income for Artists program (2022 – 2024) and a convening of advocates from across the U.S. (July 2024). In the end, this document offers the notion of a ‘crip coin’ as an essential currency for the future of the cash movement.

Suggested citation: Gotkin, Kevin. (2024). “Crip Coin: Disability, Public Benefits, & Guaranteed Income.” Creatives Rebuild New York.

About the CRNY Guaranteed Income for Artists Program

Creatives Rebuild New York (CRNY) was a three-year, $125 million investment in the financial stability of New York State artists and the organizations that employ them. CRNY’s funding was anchored by $115 million from the Mellon Foundation, with $5 million each from the Ford Foundation and the Stavros Niarchos Foundation.

CRNY provided cash and jobs to 2,700 artists whose primary residence is in New York State through a Guaranteed Income for Artists Program and an Artist Employment Program. These programs worked to alleviate unemployment of artists, continued the creative work of artists in partnership with organizations and their communities, and enabled artists to continue working and living in New York State under less financial strain. CRNY aimed to catalyze systemic change in the arts and cultural economy, recognize the value of artists’ contributions, and reshape society’s understanding of artists as workers who are vital to the health of our communities. Through its multifaceted initiatives, CRNY sought ways to move beyond the centrality of artistic output to value the humanity and wholeness of the artists’ lives.

This report draws insights from the CRNY Guaranteed Income for Artists Program that gave 2,400 New York artists $1,000 per month for 18 months. To learn more about CRNY’s other work, see CRNY’s website.

CRNY’s programs were demonstrations. This means that research and evaluations are integral to the organization’s values and goals. As such, this report is one among many publications CRNY supported to leave evidence of the programs’ design, process, implementation, and impact.

This report contributes to CRNY’s commitment to conducting a range of research, advocacy, and narrative change efforts with a strong commitment to equitable evaluation practices and artist-centered storytelling. It also helps serve several of the recommendations from CRNY’s Guaranteed Income for Artists Working Group made up of administrators of programs providing unrestricted cash and members of the larger GI field.

Please note that CRNY ended its programmatic work in December 2024.

Goals

This report seeks to:

- Collate and advance existing work on this topic

- Contextualize the contemporary cash movement with public benefits as a key backdrop

- Explain the importance of protecting access to public benefits

- Advocate for the role of disability organizing to the cash movement

- Identify existing and emergent tools for protecting access to public benefit programs

- Recommend pathways for future cross-movement work in GI and disability organizing

This document is written for disabled organizers and advocates, cash movement organizers, administrators, and researchers. It is not intended to inform an individual’s participation in a guaranteed income program.

About the Author

Kevin Gotkin is an access ecologist, facilitator, and researcher. They served on the Creatives Rebuild New York Outreach Corps in early 2022 and joined the organization as Artist-Organizer later that year. They have been working in the movement for disability artistry since 2016, when they co-founded Disability/Arts/NYC with Simi Linton. Their university-based teaching and research includes a Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania in 2018 and a Visiting Assistant Professorship (2018-2021) in NYU’s Department of Media, Culture, and Communication, where they previously received their B.S. (2011). Kevin’s performance and curatorial work has been featured at Lincoln Center (An Evening of Access Magic 2024), in nightlife organizing with the REMOTE ACCESS party collective, and in a forthcoming debut book. They have helped steward the Critical Design Lab (2022 United States Artist Award) and Creative Time’s 2021 Think Tank. They write the weekly newsletter Crip News.

Acknowledgments

Maura Cuffie-Peterson, Naja Gordon, and Isaiah Madison made CRNY’s Guaranteed Income for Artists program run. None of this would be possible without Maura’s leadership, Naja and Isaiah’s brilliance, and the whole CRNY team’s kindness, generosity, and support.

Thanks to Kathrine Cagat, Kimberly Drew, Jennifer Kellett, Michael Roush, and Chelsea Wilkinson for their generous and rigorous feedback. Additional thanks to all the participants of the July 2024 Crip Coin gathering.

Key Terms

What is guaranteed income?

Guaranteed income, sometimes called guaranteed basic income, is a regular cash payment with no strings attached. It seeks to create an ‘income floor’ so that people can meet their basic needs. ‘Universal basic income’ typically refers to a cash payment that is offered to every member of a community whereas a ‘guaranteed income’ is a targeted cash payment for a specific group of people. For our purposes, we’ll refer to ‘the cash movement’ to refer to the overall field for unrestricted direct cash transfers in the U.S.

For more about definitions of this field, see the “Everyone is Essential! Guaranteed Income” course developed by Art.coop, CreativeStudy, and Creatives Rebuild New York, written by Maura Cuffie-Peterson, Emma Guttman-Slater, and Eshe Shukura; and the Jain Family Institute’s 2021 toolkit, “Guaranteed Income in the U.S.”

What are public benefit programs?

Public benefits are government assistance programs that help people meet their basic needs, such as paying for housing, health care and insurance, food, utilities, and more. Sometimes these are referred to as ‘government benefits,’ ‘welfare programs,’ ‘safety net programs,’ or ‘entitlements’ (when anyone who meets certain eligibility requirements can receive assistance). Public benefit programs work at the federal, Tribal, state, and municipal levels (and sometimes as a collaboration between these types of government). They are publicly funded.

Why does the term ‘benefits’ refer to people’s basic needs? Its usage can be traced to the Social Security Act of 1935 that produced “a system of Federal old-age benefits” and to the growth of employment-based health insurance in the 1940s that expanded the ‘benefits’ of having a job.

How is ‘disability’ defined?

Disability communities generally use 2 primary definitions:

- The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) defines a person with a disability as a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activity. This includes people who have a record of such an impairment, even if they do not currently have a disability. It also includes individuals who do not have a disability but are regarded as having a disability.

- The Social Security Administration (SSA) defines ‘disability’ as the “inability to do any substantial gainful activity” due to a “medically determinable” physical or mental impairment that has lasted or is expected to last for a continuous period of at least 12 months.

The history of these definitions tells us a lot about the issues explored in the rest of this report.

Efforts to define ‘disability’ have long been instrumental in assigning social roles about who should produce income and who is ‘deserving’ of public aid. We see this legacy codified in the SSA’s definition above, used to determine the eligibility of millions who need support to survive, as a barrier to employment. Disability can be understood as a problem about a category within the administrative state.

Because definitions of disability have such a direct connection to the distribution of resources in the U.S., the measures for determining disability status have sought seemingly extrinsic and objective evidence about a person’s body and mind. But the project of maintaining the so-called scientific knowledge about a person and their environment has been an ideological project of its own, covering for the power over land and life.

Twinned processes of medicalization and dehumanization have afforded settler colonialist projects their deadliest weapons. In particular, novel medical diagnoses for ways to live that challenge white supremacist land ownership have justified the displacement of Indigenous people across Turtle Island, the legality of chattel slavery to build the settler nation, and the ongoing struggles to simply speak the truth of these histories.

The Disability Rights Movement that began in the latter 20th century in the U.S. seeks to expand what ‘disability’ means and insulate it from the harms of medicalization that form the living history of disability. Some cultural historians, disabled artists, culture bearers, scholars, and organizers have claimed disability as a source of community and identity. The cultural model of disability allows us to understand that the changing language about disability is more important than a one-size-fits-all definition. You’ll notice, for example, that through this report, we use ‘disabled people’ instead of ‘people with disabilities’ as an intentional alignment with ‘identity-first’ language. Similarly, we use the word ‘crip’ in the title of this report because it is a term that signals an intentional commitment to disability communities through the reclamation of a pejorative term for a disabled person.

Newer cultural and political identifications sometimes assume that disability is a more unifying category than it actually is. A popular claim that disability is ‘the world’s largest minority’ implies that disability can be compared to other, often racialized, categories. This diminishes an urgently needed understanding of disability as an intersectional and structural component of society.

In creating important anti-discrimination protections for disabled people in public life, disability organizing has often left the key mechanisms of ableism unchallenged. Disability is a cause and consequence of poverty, which means we cannot comprehensively define it apart from the wider set of conditions that generate and maintain poverty. In the mid-2000s, the framework of Disability Justice emerged to widen the single-axis focus on disability that has excluded multiply marginalized disabled people.

What the Harriet Tubman Collective called ‘disability solidarity’ in 2016 is an understanding of how disability is inherent to movement work that might not seem related to disability. For example, the struggle to end police violence, they wrote, “should work to undo racism and ableism and audism, which make Black Disabled/Deaf people prime targets.” This new paradigm models how all work toward more just futures can work in solidarity with disabled leadership.

The number of people who are drawn to disability as an identity is considerably smaller than the number of people who use disability public benefit programs. This is important to keep in mind because many people with disabilities cannot risk being understood as ‘disabled’ if it compounds others barriers to accessing social insurance. ‘Disability pride’ is often foreclosed to those most impacted by the punishing realities of using a safety net program. In this report, disability and disabled people refer to those who qualify for public benefit programs because of a disability and those who draw upon disability as community, history, and politics.

Racism, Medical Care, and Access to Disability Benefits

Some algorithms and instruments used to determine organ function and pain levels include adjustments for the race of a patient, codifying social determinants of health as innate physiological differences.

To determine lung function, for example, patients blow into a device called a spirometer. The results are used to interpret lung function and diagnose and monitor pulmonary diseases. The use of race to determine ‘normal’ lung function has had a significant impact on access to medical care. The model assumes that Black adults and adults of Asian ancestry have smaller lung capacities compared to white adults, which has led to the lack of diagnoses and treatment for pulmonary diseases among these groups.

In a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine in May 2024, researchers found that the classification of lung impairment among Black people in the U.S. would increase 141% if lung function equations were race-neutral, which the Global Lung Function Initiative, American Thoracic Society, and the European Respiratory Society all recommended in 2023. According to the research, “annual disability payments may increase by more than $1 billion among Black veterans.”

The connections between racism, ableism, and public benefits are not abstract concerns. They help us explain how the institutions meant to address disparities in wellbeing are instead maintaining them.

Part 2: Cash in Context

Guaranteed Income and Public Benefits

In July 2024, OpenResearch published one of the most comprehensive studies of cash in the U.S. The participants’ average household income was $29,900, or about 116% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) for a family of 3. If we look at the largest public benefits program in the U.S., Medicaid/the Children’s Health Insurance Program that enrolled about 77.3 million people or 23.5% of the population in 2022, we find a similar household income: in most places, the program covers families that earn up to 138% of the FPL. Although it is difficult to gather the data that reflect the overlap in precise terms, GI programs are often designed to reach those who are also eligible for public benefits.

While some benefits provide direct cash assistance, they differ from GI programs in what is required of beneficiaries to become and remain eligible for aid. The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, for example, which serves nearly 2 million people (about 75% of whom are children), requires that adults hold a job or participate in “work activities” like job readiness or on-the-job training programs. GI, on the other hand, is unconditional and unrestricted: programs do not require participants to submit documentation about employment or how the cash is used.

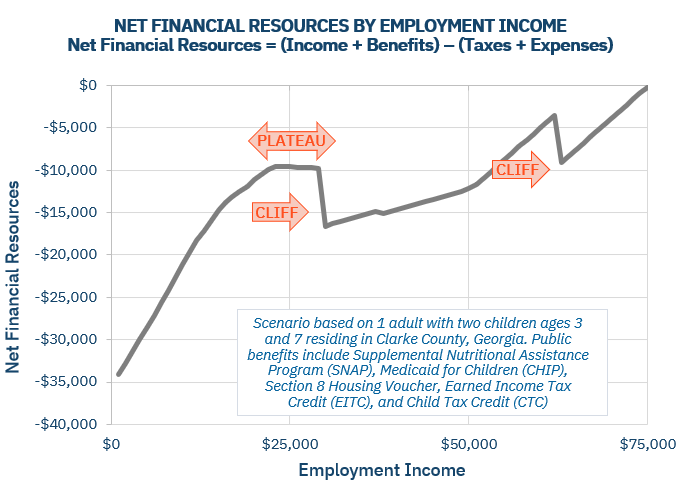

This conditionality of assistance is one way the public benefit programs contribute to economic immobility they are meant to alleviate. The ‘benefits cliff’ is another common example.

Source: “What are Benefits Cliffs?” by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

When a working family starts to earn more income, such as an increased hourly wage, these new earnings can put the family over the income eligibility limit for public benefit programs and leave the family worse off or no better than before the wage increase. In the example above prepared by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, a single parent of two children would face two precipitous drops in net financial resources as they earn more money. Even small incremental changes to a worker’s income can present a clear and direct threat to a family’s self-sufficiency. For another example that looks at how the cliff changes with a single mother’s incremental wage increases and the age of her children, see the Arlington Community Foundation’s “Sandra” model.

Unfortunately, the increase in income from participation in a GI program contributes to these same kinds of adverse effects. The Denver Basic Income Project’s Interim Report from October 2023 showed that a sizable portion of their participants used benefit programs, especially Medicaid and SNAP:

2 participants in the Denver program withdrew from the program after the first payment “citing challenges with the public benefits they receive. 1 participant withdrew from the Creatives Rebuild New York program.

While it would seem that there is only a handful of people reporting adverse effects to their public benefits, we have several reasons to believe that the available data do not offer an accurate sense of the scale of the problems:

- Some GI data explicitly exclude participants who use certain benefit programs. In the OpenResearch study cited above, for example, anyone who receives Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or lives in public housing was ineligible to participate.

- Some would-be GI participants choose not to apply when they know their benefits would be adversely affected. This is also true for people who are in the midst of a benefits determination process and can foresee the difficulties of withdrawing from a GI program in order to protect access to a new benefit program based on their pre-GI income and resource levels.

- The large scale of negative experiences using a public benefit program has also led to distrust of GI programs. People who believe their cash transfers could be clawed back or taxed are not likely to want to offer data about their lives or sensitive personal and financial information.

- Additionally, one important way GI programs must adhere to the IRS’s definition of a ‘gift’ (so that the transfers are not taxed) is by demonstrating a ‘disinterested’ relationship to program participants. This often means the organization that administers a GI program cannot also conduct research through direct engagement with participants.

So while we know in a broad sense that GI is focused on people already involved in anti-poverty programs, we are missing data necessary for a more accurate scope of the interactions between cash and public benefits.

These issues reveal that benefit programs’ restrictions make GI too good to be true in some instances for people who could benefit from no-strings-attached cash. When GI is not designed with public benefits in mind, some people simply can’t afford to participate in new cash programs.

Safety net programs form a major component of the context into which cash programs are emerging. And thus, conversations about GI often relate to existing safety net programs in several ways:

- Some argue that GI should replace public benefits.

- Andrew Yang’s 2020 bid for the Democratic Presidential nomination proposed “The Freedom Dividend” as a universal basic income. His plan projected savings on federal benefits expenditures because “people already receiving benefits would have a choice between keeping their current benefits and the $1,000, and would not receive both.” This is a good example of how GI and safety net programs are compared to suggest that GI could replace existing welfare program.

- Not all advocates support a model that replaces public benefits, but the vibrant debate about targeted versus universal models itself reflects different responses to the current challenges with the public benefits systems. GI has emerged with unique political expedience when these problems seem too difficult to fix, in particular for the way it might move beyond questions of ‘deservingness’ for public aid that have long beleaguered eligibility determination processes.

- Some advocate for reform of existing public benefit programs to act more as GI.

- The Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program is the largest federal housing assistance program, helping approximately 2.3 million households rent units in the private market each year by issuing a subsidy to landlords on behalf of eligible households. Because of the arduous process involved in working with landlords through public housing authorities, about 40% of voucher-eligible households are unable to find a unit that passes required inspections with a willing landlord.

- In 2023, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) issued a call for partners for a Direct Rental Assistance pilot that would issue assistance directly to households in monthly payments, thereby reducing a large source of administrative burden that keeps eligible households from getting the assistance they need. Citing the simplicity of the economic impact payments distributed by the federal government early in the Covid pandemic, HUD and its partners are testing this model in a multi-year, multi-site study.

- This is a good example of how agencies administering existing benefit programs are learning about the advantages of direct cash transfers to streamline their programs, reduce waste, and generate better outcomes for beneficiaries.

- Many advocates cite existing public benefit programs when making the case for GI.

- Across the U.S., GI organizers are formulating storytelling and narrative change campaigns to inform the public about the power of regular unrestricted cash transfers. One of the ways they introduce the concept is by citing a long tradition of issuing cash to those in need via programs that weren’t called “guaranteed income” in their time.

- For example, in the “Everyone is Essential!” course about guaranteed income developed by Maura Cuffie-Peterson, Emma Guttman-Slater, and Eshe Shukura in partnership with Art.Coop, Creative Study, and Creatives Rebuild New York, an introductory video explains how Congress passed The Mother’s Pension as the country’s first welfare program for distributing monthly cash payments to single mothers from 1911 through 1935. This was followed by significant expansions of cash transfers in the New Deal and the G.I. Bill.

- In a plenary session at the 2024 Basic Income Guarantee Conference, organizers noted the influence of the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO), a group led by Black women who brought attention to the punitive effects of benefits programs and helped Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. formulate his well-cited call for a national guaranteed income. The NWRO and Ruby Duncan, one of the NWRO’s key leaders in Las Vegas, are the subject of Hazel Gurland-Pooler’s 2023 documentary Storming Caesar’s Palace.

- Many GI advocates also cite a more recent example of the American Rescue Plan’s improvements to the Child Tax Credit (CTC) that lifted 5.3 million people, including 2.9 million children, out of poverty. When ARPA temporarily made this credit fully refundable in 2021, it was expanded to people with little or no income who typically don’t owe any taxes and therefore don’t benefit from tax credits. Additionally, the law enabled families to receive the relief as monthly payments similar to GI (and similar to child allowance programs in other countries). The success and reach of the expanded CTC provides evidence to support larger scale unrestricted cash programs..

- In explaining a seemingly new concept, GI advocates point to historic precedents, evidence, and outcomes from public benefit programs.

These examples demonstrate that public benefits are often already understood as the backdrop for today’s cash movement. In fact, some parts of the federal bureaucracy rely on systems that were devised to compare benefit programs with unrestricted cash assistance. The Transfer Income Model (TRIM) is a data modeling program designed in 1969 by members of the President’s Commission on Income Maintenance Programs. According to the background information for the current version, “The commission originally used [the model] to simulate universal income-conditioned transfer programs that were being considered as alternatives to the existing welfare programs.” Since then, many federal agencies, such as the Treasury Department and the Office of Economic Opportunity, have helped support the development of this resource and use it for their own purposes.

Thus, it may not be an exaggeration to say that contemplation of universal basic income forms part of the administrative basis from which federal benefit programs operate. This points us to a key question driving this report:

Given the many ways that cash and public benefits are deeply linked, why do GI programs do so little to protect access to public benefits for their participants?

The Enduring Legacy of the NWRO

Source: Jack Rottier Collection/George Mason University Libraries

The National Welfare Rights Organization (1966 – 1975) organized hundreds of local groups and over 20,000 people, mostly Black women. It was born out of earlier Black feminist organizing in the 60s that built power among welfare recipients. Through lobbying, direct action, and litigation, the NWRO called for an adequate income for women and children.

The NWRO addressed the racist legacy of New Deal assistance programs. The 1935 Social Security Act explicitly barred agricultural and domestic workers (half of the U.S. workforce) from benefits, minimum wage, and overtime laws. These workers were largely Black and Brown, including a significant share of Black women working in private household service. This set a standard of exclusion for later legislation, including the 1938 Fair Labor Standard Act, and forms a core of the struggle for protections and fair pay for today’s devalued workers.

In 1972, Johnnie Tillmon, one of NWRO’s leaders, wrote an iconic article for Ms. Magazine titled, “Welfare is a Women’s Issue.” In it she states: “The truth is, a job doesn’t necessarily mean an adequate income.” But the punishing design of welfare was worse. Reflecting on things like “man-in-the-house” rules that barred any able-bodied adult man from being present in a household that received welfare, Tillmon wrote: “Welfare’s like a traffic accident. It can happen to anybody, but especially it happens to women.”

Guaranteed income became part of the civil rights movement because of leaders like Johnnie Tillmon. NWRO organizers taught Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. about the limitations of employment as a form of social insurance. In so doing, they demonstrated solidarity among many different groups affected by the inaccessibility of employment. “We must create incomes,” MLK Jr. said in his famous 1967 “Where Do We Go From Here?” speech, for “those at the lowest economic level,” including “the aged and chronically ill.”

Tillmon and the NWRO saw what they called “Guaranteed Adequate Income” as the front-line of women’s freedom and its intersections with other groups marginalized by the centrality of work to economic stability. And in this tradition, GI emerges to challenge the ways public benefits programs trap people in poverty. The NWRO leaves us a legacy of movement work that can transcend the limits of single-issue organizing that often excludes BIPOC disabled people.

The Key Roles of Disability

Disability is more than a minority population that today’s GI programs seek to reach. Many aspects of the cash movement are already influenced by disability.

- Disability is an impetus for cash organizing.

- The contemporary swell in GI programs was largely activated by the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, a mass disabling event that continues to have an outsize role in the lives of disabled and immunocompromised people, and those most impacted by barriers to health care. The pandemic is revealing difficult truths about health disparities, but GI programs point to promising new forms of repair.

- Beyond addressing the unique conditions of Covid, GI programs often identify health outcomes that suggest ways to interrupt the mutually reinforcing nature of disability and poverty. The 2024 preliminary report from CRNY’s GI for Artists program, for example, showed that “participants reported feeling\ down, depressed, or hopeless nearly every day at a 39% lower rate than those who did not receive guaranteed income payment.” With about 1 in 3 participants identifying as caregivers, cash created a secondary network of influence: “Artists receiving GI were significantly more likely to provide care to kids or to adults who were elderly, ill, and/or disabled.”

- Many other commonly reported outcomes of GI programs also involve disability. Increases in worker agency and safer working conditions, for example, highlight cash as an effective buffer against the racialized ways that hazardous work affects workers’ health.

- The history of disability benefits demonstrates the need for no-strings-attached cash assistance.

- Some public benefit programs specifically focus on supporting disabled people. 62% of disabled people in the U.S. between the ages of 16 and 64 are not in the labor force, with even higher percentages among people with cognitive and ambulatory disabilities and those who use independent living and personal care support services. For these groups, programs like SSI, Medicare, and Medicaid are essential for survival.

- However, the strict limits on assets and income to remain eligible for support mean that disabled people are triply failed: by the widespread inaccessibility of employment opportunities, by the public programs meant to help those who cannot hold jobs, and by GI programs that render them effectively ineligible to apply when access to long-term disability benefits would be on the line.

What today’s cash movement is building is what disabled people desperately need but too often can’t access.

Disabled people are disconnected from today’s cash movement. One cause of the disconnect is the arduous work involved in maintaining eligibility for programs like SSI. This time and energy could be directed toward collective power-building and leadership of cash organizing. Disabled people hold a great deal of lived expertise about the minutiae of program administration and implementation, but they don’t find accessible pathways to connect with movement leaders.

The professionalization of the cash movement also reinforces the exclusion of disabled people. Many disabled organizers do not have access to budgets that would allow for travel to conferences. If their powerchairs were damaged in air travel, a staggeringly common phenomenon, SSI limits would prevent them from organizing a fundraising campaign without the use of someone else’s bank account. Additionally, people with intellectual and development disabilities are often left out of spaces that don’t use plain language.

In today’s cash movement, public benefit users experience confusion, trepidation, and, in some cases, loss of access to resources when participating in GI programs.

Over 50 Years of Supplemental Security Income (SSI)

In a televised address in 1969, President Richard Nixon unveiled a series of domestic anti-poverty policies. Central to them was a federal basic income with work requirements and incentives. The plan faced bipartisan opposition and failed to become law, but one element survived: an increase in social security benefits that later became the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program.

SSI began in 1972 when Congress federalized disability-specific programs mandated in the 1935 Social Security Act that were previously administered through a maze of state and local administrative agencies. The Social Security Administration (SSA) converted over 3 million disabled people’s benefits into the new SSI program and began distributing monthly payments in 1974.

Eligibility for SSI is complex. One must submit an application to certify that they:

- are ‘aged,’ blind, or disabled,

- have limited income and resources,

- be a citizen or documented noncitizen,

- cannot leave the U.S. for more than 30 consecutive days,

- are not confined to a publicly funded institution like a hospital or prison,

- must apply to other benefits for which they may be eligible, and

- give SSA access to their financial records.

Only about 36% of SSI applications are approved after initial review. Of the people who wait months to appeal the first decision, only 13% then get approved. Of those who then wait much longer for another review, 51% are approved.

The maximum monthly SSI payment is $967 for an eligible individual and $1,450 for an eligible couple in 2025. The average payment in January 2024 was $698.

Individual SSI recipients cannot earn more than $1971 per month (and the more they earn, the more is taken out of their SSI payment), nor can they own more than $2000 in assets or savings. While the Affordable Care Act expanded Medicaid eligibility with no asset limits on the federal level, the SSI limits haven’t been updated for 35 years. So while other benefit programs incentivize or require work, SSI makes work effectively impossible.

Additionally, SSI calculates “in-kind support and maintenance” to reduce benefits. If someone lives with family rent-free, the SSA will calculate the value of the rent to reduce a benefit. Until 2024, the food that someone else in a household shared with an SSI recipient was also calculated this way. Any money into an SSI recipient’s bank account, even if it is quickly transferred elsewhere, will reduce the benefit amount. And if two SSI recipients are married, their income and resource limits are lower per person than if they were an individual recipient.

As a result, SSI recipients experience barriers to moving (given the cost of security deposits, upfront rents, and moving costs that often exceed $2000). SSI effectively bars marriage equality for disabled people. SSI recipients can’t even set up a GoFundMe to get the funds they might need to fix an accessible vehicle or their home.

SSI is explicitly framed as a program “of last resort.” The arcane process of determining whether a disabled person might have any other forms of support to survive traps disabled people in poverty, exacerbates their disabilities, and severely curtails their quality of life. For some, SSI is also how they qualify for Medicaid that will pay for significant disability-related expenses like powerchairs or costly medications that are rarely covered by employer-sponsored health insurance plans. Access to SSI is a matter of life or death: 109,725 people died while waiting on an appeal of their SSI application between 2008 and 2019.

And SSI is astoundingly wasteful with public funds: Between 2010 and 2020, the SSA paid more than $390 million in plaintiff’s legal fees after federal judges found the agency improperly denied disability claims. In 2020 alone, the SSA paid more than $51 million to attorneys in its administrative courts.

The 7.4 million people who receive SSI could benefit immensely from GI programs. But in most cases, GI payments are calculated as income for SSI eligibility and SSI payments are significantly reduced or eliminated as a result. Because most GI programs are temporary, SSI recipients often decide they cannot risk losing their benefits in the long-term. This population has been exposed to harm in the public benefits system for decades and should be some of the most important people to reach with the transformative power of cash.

A note about SSDI: You may be familiar with another federal program, Social Security Disability Insurance. SSDI is funded by payroll taxes and is tied to work history. It also interacts with GI, but has a distinct history, eligibility process, and political context.

What is needed?

Benefits interactions are often treated as a question of GI program implementation. This misses an important opportunity to understand and elaborate the shared values and desired outcomes across new GI and existing safety net programs.

Those most impacted by GI programs’ benefits interactions are often the people who most need what the cash movement can offer.

GI advocates, administrators, and participants need more support in situating programs within the landscape of existing public benefit programs.

- In the design…

- It can be difficult to discern how many potential participants use public benefits and which programs are most common. Some administrators face short deadlines for program design that don’t allow for the chance to identify existing data, connect with experts, and devise pre-launch strategies for mitigating benefits loss. Careful attention to benefits interactions needs to begin long before a program starts to ensure consistency in all the following aspects.

- In the implementation…

- Administrators often forge new collaborations with benefits counseling partners to help applicants understand how their benefits may be affected if they are selected for a new program. There are many different kinds of benefits counseling models available, but these differences take time to understand.

- Some programs designate ‘hold harmless funds’ to offset unforeseen consequences of GI participation, such as unexpected benefits loss. But the parameters for these funds are often undefined and/or not widely publicized for prospective participants. Hold harmless funds could play a bigger role in navigating benefits interactions if they are designed in detail from the beginning. Ideally, strong protections for benefits access would make these funds unnecessary.

- Additionally, GI programs have an opportunity to connect those who are not selected for a program to other public benefits programs they are eligible for. Research has found that 1 in 6 adults in immigrant families with children avoided public programs in 2022 because of green card concerns. Advocates can align their implementation processes to support the movement to increase access to benefits. The result of this kind of solidarity organizing could have significant impacts on poverty: One study calculated that if everyone who was eligible for a public benefit program was enrolled, poverty would be reduced by 31% overall and 44% for children.

- In research…

- The research and data that are emerging from 130+ GI programs around the U.S. can tell us a great deal about safety net programs. For example, several studies have shown how cash supports workers by situating GI in a moral economy where workers’ health and safety matters. Cash gives workers the security to organize for better working conditions, start their own businesses, and engage in essential unpaid labor like family caregiving. At the same time, cash programs could offer data about the sizable portion of the population who cannot hold jobs in workplaces that are inaccessible, which might in turn support efforts to reform programs like Supplemental Security Income (SSI).

- In advocacy and narrative change…

- GI movement work is well-positioned to build strategic coalitions with safety net program organizing and advocacy for coordinated messaging about the potential of cash. These coalitions would lead to better racial, class, and disability analyses that can identify opportunities for solidarity, such as the national campaign to lift the SSI asset limit. With so many public benefits affecting young people, there is also a natural opportunity to support youth organizing and self-determination as people age out of benefits support.

- In power-building with GI program participants…

- The Creatives Rebuild New York Guaranteed Income for Artists Program offered a unique form of direct support to individual artists. After the 18-month period of distributing $1,000 per month to 2,400 artists, all artists were invited to advocacy workshops. Several artist collectives and organizations were granted funds to do teach-ins on GI in their own communities. And the CRNY Artist Power Building School brought together artist-participants as Fellows with Political Education Partners and a 4-part workshop series to collectivize, spread knowledge about economic justice, and foster base-building within the guaranteed income movement.

- As CRNY’s participants have demonstrated, artists and culture bearers help sustain and energize economic justice movement work. These artists translate collective action into stories and campaigns that can reach new audiences and partners. They expand the forms of research and evaluation. Their service to their communities holds the transformative potential of the arts to improve well-being and pursue critical dialogues. The cash movement needs more support for directly engaging program participants to lead and sustain advocacy.

Public benefit programs already form the backdrop for today’s cash movement. Expanding our understanding of how they relate will help us get more resources to those who need it most and leave evidence for more impactful GI models. Public benefit programs can help elucidate various political orientations within the cash movement for better and more strategic coalitioning across different scales (federal, state, and local).

Part 3: How to Increase and Protect Access to Public Benefits Programs

In July 2024, CRNY’s Kevin Gotkin (Artist-Organizer) and Maura Cuffie-Peterson (Director of Strategic Initiatives for Guaranteed Income) organized a convening following the Basic Income Guarantee Conference in San Francisco. The gathering brought together 42 disability organizers, artists, and policy experts to discuss disability power-building and public benefits access in the cash movement. The hybrid event used disability-centric facilitation design to model access as a strategic tool for what the group was prompted to imagine about the future of cash organizing.

As Michael Roush, Director of the Center for Disability-Inclusive Community Development at the National Disability Institute, pointed out, our gathering took place the same week as the 34th anniversary of the passing of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). While many know this landmark piece of legislation as a suite of anti-discrimination protections, it also names “economic self-sufficiency” as a primary goal. Given the swell of cash pilots and programs since 2020, GI is well-positioned as a powerful tool to continue this legacy of the ADA.

During the convening, we prompted the group to identify tools and techniques that are currently available to protect benefits access as well as dream big about a cash movement that is led by principles in disability organizing. And in response, attendees helped us understand new and better questions we need to be asking.

Trinh Phan, Director of State Income Security at Justice in Aging, invited us to understand a functional system as one that effectively allocates resources to those most exposed to harm. She asked, “What is the form of getting to where we want to be? Is it a bridge? An accessible bus? A ride-share driven by a disabled gig worker who is paid fairly and has portable benefits? A disability-led, artist-driven cash movement can take up these questions to continue what our convening started.

We’ve organized the group’s insights in the section below. We sought to give tribute to and build upon a growing amount of documentation from cash advocates who have previously studied and made recommendations about limiting benefits interactions while distributing cash. You can find these in the ‘Resources’ section near the end of this report.

1. Collaboration with disabled experts

There was one tool our group cited more than any other: Disabled people’s access to decision-making. When disability organizers are engaged from the start of a GI program, their expertise can be a resource through a program’s entire life cycle.

Building the basis for respect, dignity, and trust is essential, and it may take some time to find the right organizers and set the parameters for a successful collaboration. The knowledge that can come from this work is extensive. For example, program staff might learn the differences between SSI and SSDI through people’s lived experiences.

This requires dedicated funding. Accessibility must be a line item in every budget. Access workers like ASL interpreters, captioners, and audio describers need to be paid fairly. They also need ample time for preparation. One of the best ways to do this is to hire an access coordinator who can plan the access features of a whole design process, ensuring consistency among the access worker team so that they can build and refine their interpretations over time. When planning for Deaf access, Deaf people must be in charge.

Working closely with disabled experts leads to virtuous cycles of accessibility. For example, plain language ensures the accessibility of written materials for a wide range of people, including those with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Plain language has many other benefits, such as making an organization’s internal communications more accessible to new staff and making it easier to ensure language access at events and meeting with ASL and other real-time language interpreters.

In the CRNY Plain Language Project, we held a focus group as one of the final stages in our development of plain language materials. Through this process, we made sure that the people who would use these materials have a say in how they were made. This also allowed us to understand what language made sense to people who were new to the concept of GI. According to the focus group participants, GI was easiest to understand when we explained it as a new kind of benefit program.

These kinds of collaborations with disabled experts offer key lessons for the design of cash programs that can work better for everyone.

2. Data gathering and research

There is a robust and growing literature about GI, but ‘disability’ is often figured only as a kind of health outcome in research. While the effects of cash on disability are important to track, this is not the only kind of data the field should be interested in. It is crucial to factor disability status/identification into data-gathering efforts to accurately understand how disabled people are impacted by GI programs.

GI research is uniquely positioned to offer insight into how cash interacts with safety net programs, but people who use public benefits are too often sorted out of research efforts entirely. For example, OpenResearch’s Unconditional Cash Transfer Study, touted as “the country’s most comprehensive study on unconditional cash,” treated anyone using SSI, SSDI, or Section 8 as categorically ineligible to participate in their study’s sample. The study’s monthly $1,000 transfer was “large enough that layering on a basic income would reduce the relevance of the study.” The number of excluded individuals, they claimed, was low enough that it “should not introduce meaningful selection bias” (p. 13 – 14)

But just the opposite is true: collecting stories from people who use public benefits is all the more important because they would be uniquely impacted by the cash transfers. These complex interactions are made invisible and many people are barred from the benefits of cash when our research practices fail to capture these experiences. It is imperative, then, that researchers and evaluators gather data about disability and public benefits, model best practices, and share what is learned.

3. ABLE Accounts

ABLE accounts are tax-free savings accounts for people with disabilities that help protect a person’s eligibility for public benefits. The Stephen Beck Jr. Achieving a Better Life Experience (ABLE) Act, signed into law by President Obama in 2014, amended the IRS code to create a new kind of 529 savings account similar to the 529 College Savings Program. The funds in ABLE accounts are available to cover qualified disability-related expenses, including education, housing and transportation. ABLE account funds supplement, not replace, government benefits. Thus, according to the ABLE National Resource Center, “For the first time in public policy, the ABLE Act recognizes the extra and significant costs of living with a disability.”

ABLE accounts are limited to people whose disability onset before a certain age. At the time of this publication, a disability must have onset before the age of 26. Those who meet this requirement and also receive SSI and/or SSDI are automatically eligible for an account. Those who do not receive SSI and/or SSDI but still meet the age of disability onset requirement are eligible for an account if they meet Social Security’s definition and criteria regarding “functional limitations” and receive a certification from certain medical providers. As part of the Omnibus Spending Bill of 2021, the age of onset disability will increase from 26 to 45 on January 1, 2026. With this expansion, a total of 14 million disabled people will be eligible for an ABLE account.

ABLE accounts can be checking, savings, or investment accounts, with debit cards or prepaid cards (automatically considered a qualified expense). Friends, family, and employers can contribute directly to an ABLE account with the routing and account numbers or by using platforms like UGift529.com. In this way, ABLE accounts have become a more accessible version of Supplemental or Special Needs Trusts (SNTs), which are court-approved to cover disabled people’s living expenses. SNTs are often costly to establish and can make disabled people vulnerable to financial abuse at the hands of their trust administrators and/or court systems. ABLE accounts and SNTs are not mutually exclusive.

ABLE accounts do have annual contribution limits. Contributions cannot exceed the IRS’s threshold for gift tax exemption ($18,000 in 2024). If the ABLE account holder is employed and is not making certain retirement plan contributions, they can deposit an additional amount up to the individual Federal Poverty Level for a one-person household in their state of residence for the prior calendar year ($14,580 in the continental U.S., $18,210 in Alaska, and $16,770 in Hawaii). Thus, a typical limit on an ABLE account holder’s wage contributions is $32,580 (assuming no other kinds of contributions into the account, such as monetary birthday gifts or guaranteed income payments).

According to Jody Ellis, Director of the ABLE National Resource Center, there are 162,969 active ABLE account holders in 46 states and the District of Columbia. This means that only 2% of those eligible for an account are using one. GI programs can help reach people who might benefit from opening an ABLE account.

GI programs can also use ABLE accounts to protect public benefits eligibility in some cases. Deposits to an ABLE account do not count toward federal resource limits like SSI’s $2,000 resource limit. But ABLE account deposits can be considered unearned income and will affect SSI payments for the month of receipt. GI program staff should have a basic sense of these kinds of advantages and limits when using an ABLE account so they can communicate clearly with participants.

The payment platforms that GI programs use to distribute cash can also help educate and standardize practices for deposits into ABLE accounts. All of this can help with the awareness campaigns to increase the use of this important financial instrument.

4. Payment Amounts and Lump Sums

The regularity of monthly payments and the standardization of payment amounts to all program participants are often understood as hallmark features of GI. Consistency and parity are often what forms what is referred to as participants’ ‘income floor.’ But when it comes to protecting access to public benefit programs, both of these features might need to be adapted.

In some cases, a ‘lump sum’ payment of the total amount a participant receives from a program in a one-time transfer can help. This can put the income/asset limit at risk fewer times than consecutive monthly payments. In addition to protecting some benefits eligibility, new research suggests there are additional benefits of this model. For example, the Denver Basic Income Project found that the percentage of participants staying in a home/apartment they rent/own increased from 5% at enrollment to 40% at 6 months for those who received a lump sum, compared with an increase from 8% to 34% among those receiving monthly payments (p.13)

People who use public benefits often know the threshold they can earn, receive, or hold in their accounts to remain eligible. GI payment amounts are typically over these thresholds. If someone selected for a GI program were allowed to elect any amount up to the standard payment amount, however, more people would be able to enroll in new GI initiatives without fearing that they would lose access to a benefit program that might take years to re-enroll in after a GI program’s term is over.

To be clear, public benefits users should be able to retain all of the resources they need to live and thrive. But given the intractability of benefit program restrictions, it can allow some participants a greater amount of net resources if they elect a lower GI payment amount.

TANF Funds with GI Principles: Nonrecurrent, Short-Term Benefits (NRSTs)

Lump sum payments match one possible pathway for using TANF funds as a kind of GI. Some states are exploring TANF block grant funds using a “nonrecurrent, short-term benefits” (NRSTs) model. This model is limited to a crisis intervention for up to 4 monthly payments and may not “address a chronic or ongoing situation.” Because these payments are not considered ‘assistance,’ they do not trigger behavioral requirements, time limits, and data reporting required for assistance programs.

There are other benefits protection mechanisms built into NRSTs. If they are wholly state-funded, they may meet the definition of ‘assistance based on need’ (ABON) and be excluded from income determinations for SSI. They are also explicitly excluded as countable income for the purposes of SNAP eligibility determinations.

Though limited, lump sum payments could be part of a strategy to reform existing benefits using GI principles and explore the unique outcomes of GI as an investment instead of a regular payment.

5. Benefits Counseling

Benefits counseling is a common feature of today’s GI programs. In the time between being selected for a GI program and the start of their payments, participants are offered consultation sessions with experts who can help explain the effects of new income on their benefits enrollments.

In cases where it’s clear which benefit programs a GI participant pool may be using, it is important to match the counseling to the population being served. For example, if a large number of prospective GI program participants use SNAP, counseling could include a bank of resources available to everyone at any point during the program. In other cases, close 1:1 counseling sessions are a better fit for the intricacies of benefits interactions.

Presentations or workshops for participants at the start of a program can be less effective than on-demand counseling once problems arise. A change or removal of a benefit can be unexpected. In some cases, like with the Social Security Administration, agencies cannot write personalized letters to enrollees and must select a letter template that may not closely match someone’s case. This is when a counselor can be helpful as a translator of confusing letters and help a participant make a plan to navigate the crisis. Counselors can also act as news monitors, advising participants about things like changes to SNAP rules about documentation of employment status they may not encounter on their own.

Many existing counseling models focus on income, leaving participants unaware about GI programs’ effects on asset/resources limits. Similarly, counselors can miss the opportunity to identify income exclusions, such as the cost of buying or maintaining an accessible vehicle, which lower the income that is calculated for eligibility. In general, counseling should support participants to trust the counseling process, clearly understand their options, and reduce their uncertainties.

GI advocates should make a thorough plan for offering benefits counseling throughout the course of a GI program and join existing advocacy efforts to make benefits more comprehensive, human-centered, and easier to understand. Offering counseling at the end of a program can also support participants through the process of re-enrolling for lost benefits.

6. Legislative and Regulatory Tools

Working with public agency administrators and/or elected officials can sometimes produce direct protections against GI benefits interactions. In California, for example, advocates helped pass a state law that exempted GI payments when calculating eligibility for CalWORKS (the state’s TANF program) and a number of other state-administered public benefits. Similar exemptions were made in Illinois for the Cook County Promise GI Pilot. There are also sector-specific models that are worth noting, such as the Ontario Disability Support Program’s exemption of arts grants from artists’ income calculations in Canada. This approach takes time, but both of these cases establish broader applicability beyond GI payments for protecting benefits.

‘Disaster relief’ is one category that allows agencies to exempt GI payments from SSI eligibility without needing to involve elected officials or state program administrators. The Diverse Learners Recovery Fund in Chicago, for example, secured the assurance that its payments would not be calculated in many benefit programs before the program launched. In a rare example on the federal level, the Social Security Administration issued guidance on April 13, 2023 that named specific Covid-related GI programs in several states as exempt from SSI eligibility determinations. Unfortunately, these exemptions only applied through May 11, 2023, at the end of the federal public health emergency declaration.

The SSA also excludes “Assistance Based on Need” (ABON) from SSI eligibility determination. Several programs across the country have met the criteria for this income exclusion, though it’s important to note that any ABON retained into the month following a payment is considered a countable resource.

The SSA is also leading work itself to understand GI payments’ interactions with SSI. In partnership with the University of Pennsylvania and the Humanity Forward Foundation, the Guaranteed Income Financial Treatment Trial (GIFTT) tests 12 monthly payments of $1,000 plus benefits counseling for adults with cancer in active treatment against a control group that receives the typical supports available to cancer patients at their hospital. The demonstration, which will run through April 2030, excludes GI payments from income determination and as a resource during and up to 3 years after the final payment.

Fully refundable tax credits may offer a viable route for collaboration with elected officials that effectively create a GI program even if it isn’t called that. Individuals and families who earn little or nothing typically cannot benefit from tax credits that only affect a taxpayer’s over- or underpayment to the IRS. As the temporary expansion of the Child Tax Credit (CTC) demonstrated, however, a fully refundable tax credit for all is a way to issue monthly payments to low-income people without affecting benefits programs (except in the cases of egregious error). The SSA also periodically releases guidance about fully refundable tax credits, most recently advising the way state and local credits can meet the definition of an Assistance Based on Need (ABON) income exclusion for SSI.

Many of these examples were possible because these GI programs used public funding and were framed as pilot research. In the case of the CRNY GI program, the SSA determined that participants’ payments would be counted as income because the program was privately funded. As the definition of ABON demonstrates, only programs that use income as a factor of eligibility; and are funded wholly by a state are eligible for this income exclusion for SSI.

Ever-changing political contexts have a strong influence on legislative/regulatory approaches. For example, migrants’ use of public benefits, possibly including publicly funded GI programs, are grounds for denying admission to the U.S. Recent changes and uncertainty about interpretations of the ‘public charge’ rule put GI into the sets of challenges facing people seeking entry to the U.S. As a result, campaigns like KeepYourBenefits.org seek to clarify and reduce stress on migrant families.

As GI becomes increasingly litigated in the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn affirmative action in the 2023 Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard decision, GI advocates have been preparing for an increasingly partisan fight about cash programs. While work with elected officials may be affected by the changes to our political environment, some of the agencies that administer public benefit programs remain open to collaboration about GI programs. For example, the Social Security Administration’s Interventional Cooperative Agreement Program’s partnerships to “identify, operate, and evaluate interventional research” related to SSDI and SSI might be one place where GI advocates can make direct connections that could result in a better understanding of how to mitigate benefits interactions.

In its 2023 report, “Toward Economic Security: The Impact of Income and Asset Limits on People with Disabilities,” The National Council on Disability called on state and federal legislators to fund GI pilot programs targeted at people with disabilities who receive SSI and/or Medicaid. “These pilot programs must be designed in a way that protects the individual’s eligibility for Medicaid for the entire period of the pilot, suspends the SSI methodologies that would count GBI as income, and suspend asset limits to allow the individual to attain assets and access resources needed to sustain wealth building after the program ends.” (p. 90)

Part 4: Building Disability Power Toward a 'Crip Coin'

The American Women Quarters™ Program (2021 – 2025) “celebrates the accomplishments and contributions made by women of the United States” by issuing new designs for the reverse face of the quarter dollar coin. In consultation with a range of federal agencies and elected officials, the program selected the late disabled organizer and artist Stacey Park Milbern to be honored on a new coin design in 2025.

Design by Elana Hagler.

The run of coins with Stacey’s likeness is limited, so the value of the new design is more symbolic than material. The occasion thus prompts us to consider what is traded, circulated, and meant when “Disability Justice” is literally legal tender. The worth of disability remains significant when economic security is so routinely and systematically denied to disabled people. But while dollars and cents course through ableist market systems, disability communities generate and share different currencies of relationships, care, and mutual support.

It was a central goal of this report to offer some specific pathways for GI advocates to increase and protect access to public benefit programs. To conclude, let’s imagine a bigger picture about the role disability can play in the growing cash movement.

- Disability solidarity is essential for a strong coalition to advance the future of cash. Access offers a methodology for not leaving anyone behind. It models care in the immediate sphere of meetings, conferences, and workshops. Access also helps monitor what advocates and organizers need to remain engaged in the work. Disabled people are experts on cash because of the unique effects of ableist restrictions of long-standing cash programs. Solidarity looks like GI organizers amplifying disabled leaders’ calls to raise the SSI asset limit and abolish subminimum wages. For more, see the materials from CRNY’s 2023 Access Access program series.

- Public benefits are an important part of the cash movement. In New York, child poverty would fall by 52% and overall poverty would fall by 37% if everyone who was eligible for a benefit program actually enrolled, lifting over 1 million people and 365,000 children out of poverty. The cash movement grows stronger when it recognizes how public benefits already are and could be more central to the power of no-strings-attached cash payments. If GI programs can increase and protect benefits and if benefit programs can adopt principles of GI, we are building a more unified and dynamic movement ecosystem.

- A rising tide should lift everyone. If disabled people and others who use public benefit programs aren’t among the people who will be served by GI programs, the cash movement will replicate the forms of discrimination that already make benefit programs paternalistic and punitive. GI programs should work for all people.

At the 2024 Basic Income Guarantee Conference, an array of presenters testified to the transformative power of cash as a route to other kinds of services, supports, and communities. Some refer to this as the ‘+’ in ‘cash plus’ program designs. Others call it ‘magic.’ We are learning a profound and counterintuitive lesson: there are currencies besides cash that are just as important and sometimes more so. This leads us to ask about the possibilities for the proliferation of disability-specific currencies.

A ‘crip coin’ is a beautiful horizon.

Cash is one kind of currency. But so, too, is the way disabled people help each other live through the isolation of an ongoing Covid pandemic while public life has moved on. Crip coin cherishes a broad context for the lives of disabled people, including forms of survival and mutual aid that are specific to disability communities when ableism blocks access to ‘coin’ in a monetary sense. The many possibilities for disability solidarity are the crip coins our movement desperately needs.

Crip coin offers radical hope with technical guidance for the cash movement’s future directions.

Part 5: Resources

On the politics of cash and benefits:

- Althea Erickson, “I’m so over benefits,” Working Matters, Mar. 7, 2024

- Kevin Gotkin, “MLK, Guaranteed Income, & Disability,” Crip News, Jan. 16, 2023

- Kevin Gotkin, “What We’re Learning About Disability & Cash” (slide deck), Basic Income Guarantee Conference, June 8, 2023

- Johnnie Tillmon, “Welfare Is a Women’s Issue,” Ms. Magazine, Spring 1972 [Mar. 25, 2021]

On the administrative relationships between cash and benefits:

- “Direct Cash & Public Benefit Systems: Advancing solutions to address poverty and streamline support delivery” (panel recording) Basic Income Guarantee Conference panel with Jennifer Kellett, Joyanne Cobb, Ryan Ambrose, & Mary Durden, June 25, 2022

- Guaranteed Income Community of Practice, “Compiled Research: Guaranteed Income and Public Benefits,” Dec. 2021

- Amy Castro Baker, Stacia Martin-West, Sukhi Samra, and Meagan Cusack, “Mitigating loss of health insurance and means tested benefits in an unconditional cash transfer experiment: Implementation lessons from Stockton’s guaranteed income pilot,” 2020

- The Resilient Families Hub, “Lessons Learned from Direct Cash Innovations to Improve Public Benefits” (slide deck), Apr. 9, 2024

Tools/reports for protecting access to public benefits:

- Kimberly Drew and Jourdan McGinn, “Thriving Providers Project Benefits Protection Toolkit”

- Thriving Providers Project, “Benefits Guide”

- Income Movement’s Pilot Community Engagement Project, “Best Practices Toolkit: Protecting Benefits”

- Income Movement, “Protecting Benefits While Distributing Cash” (workshop recording), Nov. 2022

- Income Movement, “Protecting Benefits for Pilot Participants” (2-page primer)

- Guaranteed Income Community of Practice, “The Benefits Cliff and Guaranteed Income,” June 2021

- San Francisco Office of Financial Empowerment, Bay Area Regional Health Inequities Initiative, and Expecting Justice, “Protecting Benefits in Guaranteed Income Pilots: Lessons Learned from the Abundant Birth Project,” Nov. 2021

- “Social Safety Net Benefits Matrix 2022” & “AFN Pilot Social Safety Net Benefits Matrix,” last updated Feb. 2023

- Career Ladder Identifier and Financial Forecaster (CLIFF), Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

- Elias Ilin and Ellyn Terry, “Benefits Cliffs Across the U.S.,” part of the Policy Rules Database, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, 2021

On lived experience of public benefits:

- Joseph Shapiro, “These disabled people tried to play by the rules. It cost them their federal benefits,” NPR, June 8, 2024

- Mark Betancourt, “Inside the Kafkaesque Process for Determining Who Gets Federal Disability Benefits,” Mother Jones, Sept./Oct. 2022

- Jennifer Brooks, “I have a disability and I found a job I love. Social Security is making me pay dearly,” The Hill, Apr. 2, 2024

- Dulce Gonzalez, Genevieve M. Kenney, Michael Karpman, and Sarah Morriss, “Four in Ten Adults with Disabilities Experienced Unfair Treatment in Health Care Settings, at Work, or When Applying for Public Benefits in 2022,” Urban Institute, Oct. 11, 2023

- Bunny McFadden (The Fuller Project), “Living on the edge: why some California women try to avoid a raise,” The Guardian, May 9, 2023

- Julia Casey (FPWA), “Caught in the Gaps: How the pitfalls of cash assistance programs perpetuate economic insecurity for New Yorkers,” Jan. 2023

On disability economic justice:

- Ramonia Rochester, Elizabeth Jennings, Jeo Antolin, and Christi Baker, “Advancing Economic Justice for People with Disabilities,” 2023

- Sins Invalid, “10 Principles of Disability Justice,” Sept. 17, 2015

- Voices of Disability Economic Justice, The Century Foundation

So many stories we were told about a safety net.

– “Sunset” by Caroline Polachek

But when I look for it, it’s just a hand that’s holding mine.