Deaf and Disabled Artist Employment: Research on Work

This is the webpage version of this report. You can also access the PDF version.

Contents

Part 1: Introduction

How does employment support the lives and careers of Deaf and disabled artists in New York State?

This document offers context, data, and analysis about artists’ lives and careers in a 2-year employment program (2022 – 2024).

A Note About Language

‘Deaf and disabled artists’ indicates a range of experiences and identities. But the distinctions between identifiers are meaningful and our goal is to accurately address these complexities with care.

For example, ‘Deaf’ is a community term that references the linguistic and cultural importance of sign language whereas deafness refers to physiological experience. ‘Identity-first’ language like ‘disabled person’ emphasizes how disability can create community around the shared experiences of ableism whereas some prefer ‘people-first’ language like ‘person with a disability’ to stress personhood as the basis for discussing disability. We acknowledge the importance of these differences in the groundwork for the research below.

As explored further in the Deaf and Disability Identification data in the Study Methods section, the artists interviewed for this report identify as Deaf, Hard of Hearing, disabled, chronically ill, neurodivergent, and/or Mad.

About the Creatives Rebuild New York Artist Employment Program

CRNY provided cash and jobs to 2,700 artists whose primary residence is in New York State through a Guaranteed Income for Artists Program and an Artist Employment Program. These programs worked to alleviate unemployment of artists, continued the creative work of artists in partnership with organizations and their communities, and enabled artists to continue working and living in New York State under less financial strain. CRNY aimed to catalyze systemic change in the arts and cultural economy, recognize the value of artists’ contributions, and reshape society’s understanding of artists as workers who are vital to the health of our communities. Through its multi-faceted initiatives, CRNY sought ways to move beyond the centrality of artistic output to value the humanity and wholeness of the artists’ lives.

The focus of this report is the Artist Employment Program. To learn more about CRNY’s Guaranteed Income for Artists Program, see its program overview page.

CRNY’s Artist Employment Program (AEP) was a 2-year program (2022 – 2024) that funded employment for 300 artists working in collaboration with community-based organizations across New York State. Participating artists received a salary of $65,000 per year (commensurate with median household income in New York State) plus benefits ($18,200 or 28%) and dedicated time to focus on their artistic practice. Community-based organizations received $25,000 – $100,000 per year to support their collaborations with these artists.

The AEP selection process occurred in two stages: an application review stage and an interview stage. CRNY received over 2,700 applications in the first stage, of which 1,800 were eligible for review. Reviewers were hired from a diverse range of geographic regions and lived experiences to draw on local and cultural expertise. Instead of artistic merit, the selection included the integrity of connection, alignment between the artist and organization, and potential for impact.

98 collaborations were selected for the program. The selection process prioritized work that was led by and supported the following communities: BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color), immigrants, LGBTQIAP+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer/Questioning, Intersex, Asexual/Aromantic, Pansexual+), Deaf/Disabled, criminal legal system-involved, living at or below the poverty line, and/or living in rural areas.

CRNY’s programs were demonstrations. This means that research and evaluations are integral to the organization’s values and goals. As such, this report is one among many publications CRNY supported to leave evidence of the programs’ design, process, implementation, and impact.

This report contributes to CRNY’s commitment to conducting a range of research, advocacy, and narrative change efforts with a strong commitment to equitable evaluation practices and artist-centered storytelling. We are committed to research that centers equity in its processes and methods — prioritizing the perspectives and knowledge of program participants and ensuring that they are the ones best positioned to use or benefit from the findings.

This report helps serve 2 of the recommendations from a Working Group about artist employment composed of program administrators, advocates, researchers, and artists that CRNY convened in the fall of 2023:

- Deepen the analysis of artist employment programs nationwide, and

- Develop tools, resources, and guidance for future artist employment programs.

About the Author

Kevin Gotkin is an access ecologist, facilitator, and researcher. They served on the Creatives Rebuild New York Outreach Corps in early 2022 and joined the organization as Artist-Organizer later that year. They have been working in the movement for disability artistry since 2016, when they co-founded Disability/Arts/NYC with Simi Linton. Their university-based teaching and research includes a Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania in 2018 and a Visiting Assistant Professorship (2018-2021) in NYU’s Department of Media, Culture, and Communication, where they previously received their B.S. (2011). Kevin’s performance and curatorial work has been featured at Lincoln Center (An Evening of Access Magic 2024), in nightlife organizing with the REMOTE ACCESS party collective, and in a forthcoming debut book. They have helped steward the Critical Design Lab (2022 United States Artist Award) and Creative Time’s 2021 Think Tank. They write the weekly newsletter Crip News.

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible by Kevin Gotkin’s role as Artist-Organizer at CRNY, part of this Artist Employment Program. Bella Desai and Christopher Mulè made CRNY’s Artist Employment Program run. None of this research would have been possible without the kindness, generosity, brilliance, and sophistication of each and every member of the CRNY team.

Part 2: Contexts

This section offers critical and historical research about employment, disability, and artistry. It reviews several factors that shape how New York’s Deaf and disabled artists work, how we tell their stories, and how we organize for sustainable changes to advance Deaf and disability artistry. It is meant as a background for the interview research with participants in the CRNY employment program that follows. If you’d like to go straight to the research findings, navigate to the Study Methods and Results sections.

Disability in the arts is often perceived as a peripheral or minoritized category. As this section seeks to demonstrate, Deaf and disabled artists are in fact central to understanding the precarity and differential access to social insurance that affect all artists’ lives and work.

Work Trouble

In April 2024, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) released a new data resource called the Arts Indicators Project that provides the public “with frequently updated statistics on the health and vitality of the arts in the United States.” The project organizes large amounts of data about artists and cultural workers, including what kinds of jobs they have, which disciplines they’re in, their sex, race, ethnicity, age, how they’ve been educated, and who their teachers are.

Data about disability was missing in every aspect of the project’s framework. This absence reveals a contradiction within the largest arts funding organization in the U.S., whose mission “fosters and sustains an environment in which the arts benefit everyone in the United States.” The NEA’s practices are telling as a model for arts organizations across the country.

But this runs deeper than we might think. It doesn’t come simply from a set of choices made by some people at a given time. And ways to address it aren’t as easy as adding in some measures to existing data collection instruments.

The problem is work. When we look at 2 important terms – ‘disability’ and ‘artist’ – we find that both are defined by their complicated relationships with employment.

‘Disability’

Efforts to define ‘disability’ have been central to the evolution of the U.S. administrative state. (This is the central argument of Deborah Stone’s 1984 influential study The Disabled State.) America, as a political idea, exchanges the convictions of cooperative individuals (taxation) for the distribution of resources that guarantee a common welfare (safety net). That’s the idea, but certainly not the reality.

What we call ‘disability’ defines the difference. The physiological capacity to work has long been one way that social roles within the so-called social contract have been arbitrated on the level of the individual. Seemingly extrinsic and objective forms of evidence about a person’s body have been trusted to confer status about who should be considered an American, who can produce income, and who is ‘deserving’ of public aid.

But so-called scientific knowledge about a person and their environment has in fact been ideological cover for the power over land and life. Twinned processes of medicalization and dehumanization have afforded settler colonialist projects its deadliest weapons. Novel diagnoses for ways to live that challenge white supremacy have justified the displacement of Native peoples across Turtle Island, the legality of chattel slavery to build the settler nation, and the ongoing struggles to simply speak the truth of these histories.

The lasting legacy of this violence helps explain why the number of disabled people in the U.S. far outsizes the number of people who identify as disabled. (Organizer Mia Mingus has offered this as a distinction between being ‘descriptively disabled’ and ‘politically disabled.’) Claiming disability as an identity can create risk in the intimate spheres of people’s lives when ableism is a constitutive element of criminalization and mass incarceration, processes that also produce disability. In some cases, as with Deaf communities who identify with the cultural and linguistic formations around sign language, a generalized definition of ‘disability’ represents the very category that has been used to deny their basic rights to communication, mobility, and wellbeing for centuries.

We can glimpse some of these dynamics in the largest sources of disability data in the U.S. The Census Bureau’s annual American Community Survey, whose survey methods are not tied directly to access to resources, reports there were 44.7 million disabled people in the U.S. in 2023, or 13.6% of the population. The Social Security Administration’s (SSA) data, which is tied directly to access to resources and includes aging as a kind of disability, reports there were 71.6 million disabled people in the U.S. 2023, or 21.7% of the population.

But tarrying in these data sets is less useful for the context of this report than identifying how the question of who can work (who gives, who receives, in which economies, with what kinds of safety or risk) forms an important core of American political myth around disability.

Today, the Social Security Administration’s definition of ‘disability,’ used to determine the eligibility of millions who need support to survive, indicates the persistence of the idea that medical knowledge can solve social and distributive dilemmas. It defines ‘disability’ as a barrier to work, or the “inability to do any substantial gainful activity.” And it uses arcane administrative court procedures to assess the capacity of an applicant to perform any of the jobs listed in the Dictionary of Occupational Titles that hasn’t been updated since 1991. (See Mark Betancourt’s 2022 reporting in Mother Jones: “Inside the Kafkaesque Process for Determining Who Gets Federal Disability Benefits.”)

Disabled people are in the political fray where disability and work define each other:

- For poor and working class disabled people, work can be the cause and exacerbation of disability.

- Persistent ableist stereotypes figure disabled people as lazy or malingering. These stereotypes have evolved with the most significant legislative attempt to address them: enforcement of the Americans with Disabilities Act’s (ADA) sweeping anti-discrimination protections relies largely on a formal complaint system. This displaces the law’s intention to furnish disabled people with tools to spur access with the false notion that disabled people commandeer the judicial system for personal gain and avoidance of work.

- Accessibility of workplaces and public space tends to be imagined in terms of checklist compliance with the ADA that often fails to create meaningful and usable space for disabled people. Additionally, the cost of accessibility projects is imagined as the cost generated by disabled people’s presence in public life, fueling ongoing ableist aggression.

- Disability unemployment remains high and workplace inaccessibility remains normal. For all the ADA’s tools to create accessible workplaces, research has shown that the law has had no meaningful impact on the employment rates of disabled workers.

- Disabled scholar Allison V. Thompkins’s study of 18 years of the ADA’s impact on disabled workers showed that the law “significantly diminished the weeks worked and labor force participation of people with disabilities,” in the short-term following the law’s passage while having “insignificant impacts on both outcomes in the longer run.” (P. 31 in the second essay in Thompkins’s 2011 dissertation. She attributes these effects to courts’ weakening of the law’s key provisions and extra-judicial changes to safety net programs.)

- In another study from 2018, researchers offered a new categorization of disability in terms of ‘saliency’ to employers. They found that even after the ADA’s 2009 expansion of the scope of discrimination laws, the law had no effect on disabled workers except a “substantial improvement in hiring rates for individuals with physical, disabling conditions that were less salient to potential employers.” (P. 7 in Patrick Button et al.’s research, emphasis added.)

- Draconian limits on what disabled people can earn or own make poverty a condition of eligibility for the largest disability public benefit program, SSI. (In addition to other forms of institutionalized discrimination, like the SSI asset limit’s restrictions on disability marriage equality.)

For these reasons, disability in the U.S. is both a cause and consequence of poverty. The safety net systems meant to help those who are persistently denied access to employment have trapped tens of millions of disabled people in poverty. Even the term ‘social safety net’ itself was introduced into U.S. public policy as a new intervention into the old political problem about disability in the distributive system: to identify the state’s bare minimum obligations to the so-called ‘truly needy.’ (See historian Guian McKee’s analysis of the term. See also Althea Erickson’s writing on the way the term ‘benefits’ has developed to weaken employer’s obligations to workers’ wellbeing.)

Thus, disability strongly influences how we understand social insurance writ large. Within this portrait of disability as a structuring analytic for the U.S. administrative state, we can understand some of the limitations to employment as a tool to address economic precarity.

‘Artist’

How many ‘artists’ are there in the U.S.? 2022 data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics report 2.67 million, representing 1.67% of all workers ages 16 and older. But when employment is not the central definitional axis, it’s a radically different picture: NEA data from the same year report 129 million people, or 52% of all Americans, created and/or performed art. This discrepancy of 126.33 million artists reveals how the definition of the ‘artist’ is also formed around employment.

A great share of arts data rely on workforce categories. (In addition to the data from federal agencies, see The National Assembly of State Arts Agencies focus on the ‘Creative Economy‘ and the arts’ contribution to ‘economic recovery and resilience.’) This excludes a large number of artists, including elder and disabled artists, who don’t hold jobs and have been persistently excluded from accessible workplaces. Economic development frameworks entail the maintenance of unequal access to the resources employment can provide, especially so for disabled people. Economic development frameworks in data collection might strengthen arguments about the importance of the arts by figuring it as a sector that supports the overall U.S. economy, leaving aside intra-sector values of artistic process, democratic potential, and contribution to community/place that can ebb and flow with the intensities and swells of culture war debates. But this also leaves aside many of the key ways that artists access income and resources outside of work.

The centrality of work also limits how we try to make it better or better-suited to artists. For example, legal scholar Michelle Travis has argued that the forty-hour norm heavily influences courts’ thinking about the ‘reasonableness’ of disabled workers’ part-time scheduling as a workplace accommodation (a specific example of a “reasonable accommodation” that is penned in the ADA). (Michelle A. Travis, “Recapturing the Transformative Potential of Employment Discrimination Law,” Washington & Lee Law Review, vol. 62, issue 1 (2005): 21–36.) This is especially troubling given the large amount of research that shows how courts have had a dominant role in weakening disability anti-discrimination laws. The durability of the cultural dimensions of work makes employment uniquely difficult to make more accessible.

The definition of an artist as a worker is much smaller than the artist an identity, community member, trained expert, or other roles. Often specifying an individual, the term ‘artist’ therefore doesn’t account for work that can only be done collectively. In particular, Indigenous culture bearers use life traditions to transfer and preserve intergenerational knowledge. This is a more holistic process than an individual artistic practice. Similarly, community organizers and nonprofit workers may draw upon artistic methods or frameworks without locating their work in the arts or identifying as an artist.

Thus, the conventions and requirements of employment often do not match the vibrant and multi-faceted ways artists do what they do. This problem has been studied in various ways as a question of the alienation inherent to labor in the U.S. (i.e., whether artistry separates workers from the output and value of their labor). “Is art work or is it not-work,” organizer Carol Zou asks in a 2022 essay on the subject. Considering the idea of a public service jobs program, Zhou suggests employment can be a tool for artists’ economic security if we identify what employment cannot do and stretch “our will and our imaginations to go further, until we can see, touch, hear, taste the post-capitalist worlds that artists have prefigured.”

Given the lasting legacy of inaccessible workplaces, disability unemployment, and poverty as a requirement of disability assistance, artistry is one area where disabled people can have agency and dignity in what they make and how they live.

Disability ‘art therapy’ can be a paternalistic and inadequate stopgap for the chronic crisis of care and funding home and community-based services. At its worst, art-making is also a job for disabled people that pays federally sanctioned subminimum wages. (See January 2024 reporting in Crip News that discovered at least one NEA grantee that is a federal 14(c) Certificate Holder. In late 2024, the Department of Labor proposed the rule to end the 14(c) program.)

Still, artistry can be a liberatory source of escape from ableism, especially for those with access to disability as a source of community, history, and aesthetics. And the field of disability arts is expanding disabled people’s creation and exhibition of their work. This field is growing within the nonprofit arts world, but also in the private markets of art fairs and collectors.

The role of the ‘artist’ in disability arts is strongly constrained by the predominant whiteness of disability culture. The legacy of the Disability Rights Movement has generated unequal, racialized, and classed access to disability as a domain of study, artistry, and history. The compounding and evolving forms of dispossession that BIPOC queer and trans disabled people experience can in fact make identification with disability a risk to their education, housing, and income. Thus, initiatives that treat artists as workers are liable to be built within and uphold an exclusionary status quo.

The history of the Sins Invalid performance project shows us these problems and models the possibilities for transformative disability art-making. The collective was instrumental in developing the framework of disability justice in the U.S., which puts forward key values like intersectionality, interdependence, collective access, and collective liberation. In Skin, Tooth, and Bone, Sins Invalid’s primer on the disability justice framework, they explain why an ‘anti-capitalist politic’ is one of the “10 Principles of Disability Justice”:

“We don’t believe human worth is dependent on what and how much a person can produce. We critique a concept of ‘labor’ as defined by able-bodied supremacy, white supremacy and gender normativity.”

Employment has a strong influence on how we understand the term ‘artist’ in general. But it is also a difficult area specifically for disability solidarity organizing and efforts to address the conditions of disabled artists’ lives. To put it simply: work doesn’t work for everyone. And when work works, its success is often predicated on structural inequities.

The Role of Research and Data

Given how efforts to define both ‘disability’ and ‘artist’ encode contentious relationships to employment, the contemporary category of the ‘disabled artist’ is informalized and often ignored, as it is in the NEA’s Arts Indicator Project from the beginning of this section. But the points of contact between disability and artistry demonstrate that disability artistry is in fact broad and central – not narrow or minoritized – in the way we understand the economic realities of disabled people and artists in the U.S.

Even though disability is a natural part of the human life cycle and disabled people are in every community, even though entire political movements have organized to protect disability communities from harm and discrimination, even though disabled people have led major cultural shifts and given ‘disability arts’ increasing legibility as a field for funders and museums and educators, research about disability and the arts is woefully incomplete.

CRNY’s Portrait of New York Artists survey collected data from 13,164 artists during the application process for CRNY’s programs. The survey found that 10.2% of all respondents identified as Deaf or disabled. These data will be archived at the National Archive of Data on Arts & Culture at the University of Michigan for public use and further analysis of disability within and among the other demographic, geographic, and financial data. This is a significant catalyst for more and better ways of coming to know New York’s Deaf and disabled artists.

This report is part of a larger effort to turn the tide on data collection about disability and artistry, especially as Covid and long Covid continue to create a major swell in disability across the U.S., including millions of people who cannot return to work. When CRNY convened artist employment program administrators, advocates, researchers, and artists during the Artist Employment Working Group in the fall of 2023, knowledge-building and data-gathering efforts rose to the top of priorities for future artist employment program development.

This means realizing that the best and most accurate data live in communities and come directly from artists themselves. This is the ultimate goal for this research project. It also helps explain why the interview methods in the study below offer novel ways to understand and report on Deaf and disability artistry.

In Times of Crisis

CRNY emerged from Mellon Foundation President Elizabeth Alexander’s work on Governor Cuomo’s 2021 Reimagine New York Commission, a project “to recommend how New York could build back better and more equitably in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis.” Support for artists was part of the Commission’s recommendations about “Work and Expanding Opportunity in a Digital Economy.” The Commission’s report identified the long-standing financial hardships of arts organizations and workers that worsened during the early pandemic crisis and made the following recommendation:

“Support New York’s artists to inspire our communities during this difficult time. New York’s artists and cultural workers have faced acute hardship during the COVID-19 crisis. Difficulty finding work in the short-term results in immediate financial strain for creative workers. In the long-term, persistent underemployment threatens to divert a generation of artists to non-creative fields in order to make ends meet. When this happens, our entire community suffers, as we lose the dynamism and social cohesion that is inspired by culture. To relieve immediate hardship and enable creative workers to remain in their chosen fields, we recommend launching a Creatives Rebuild New York program. This program would support dozens of small- to mid-sized community arts organizations and more than 1,000 individual artists over the next two years, acknowledging the role of artists in invigorating local economies, providing insights, and helping find inspiration as we navigate the challenging events of our time.” (p. 36)

CRNY’s programs were designed by a Think Tank of experts from September 2021 to January 2022, informed by historical precedents like the 1973 Comprehensive Employment and Training Act. The application guidelines for CRNY’s programs were released on February 14, 2022 and applications were due on March 25, 2022.

As noted in the AEP Process Evaluation authored by Danya Sherman and Deidra Montgomery of Congruence Cultural Strategies:

“CRNY sought to move funds quickly given the level of need artists and organizations were facing during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, many early decisions, partnerships, and other elements of the program were implemented at a rapid speed and intense pace. Staff experienced a tension between this urgency and CRNY’s fundamental values, which include a commitment to providing care and support to applicants (and partners) at all stages of the process.” (p. 11)

The evaluation also noted the “structural and systemic context that artist employment programs operate in: a paucity of nonprofit livable wages, lack of protections for low-wage and contract workers, the complexity of employment law, and dysfunction of private and public benefits systems.” “[N]o single employment program,” the report goes on to say, “will be able to transform the lives and livelihoods of artists without extensive advocacy and organizing efforts for systems change in parallel.” (p. 6)

In a 2022 report about Covid and artists’ precarity, Americans for the Arts characterized the “backdrop of poverty, general inequity, and deep dysfunction in both public and private policy related to the core workforce of the [creative] sector” as an under-recognized “free fall” that became “undeniable in its severity” through the early pandemic. “[T]he impacts of the pandemic,” the authors write, “were harder, stronger, and more sustained for historically and currently marginalized groups.” (p. 2)

And we know that artistry has been an important part of Covid response. In a 2022 study of Americans’ perceptions of artists, over half of adults across all social and demographic characteristics expressed the perception that artists uniquely contribute to U.S. communities healing and recovery in the pandemic. As those most impacted by Covid, disabled and immunocompromised artists have greatly shaped collective pandemic-responsive art-making.

For these reasons, CRNY emerged for the benefit of the individual artist (as opposed to arts infrastructure or organizations alone). CRNY’s Artist Employment program used employment as the route for financial support to individuals. So while the speed of CRNY’s formation modeled a new pacing for philanthropic intervention, it also meant that there was little time to strategically situate the program in its surrounding social, cultural, and administrative ecosystems. This program necessarily emerged into an existing status quo of employment and safety net systems described in the previous section. Its expediency thus nested the immediacy of pandemic relief within the chronic and deep-rooted emergencies of artists’ economic instability.

Created during and because of the Covid emergency, CRNY took its place among nationwide initiatives to support artists in the early pandemic, including $53 billion in federal funds awarded to the arts and culture sector. According to NEA data analyzed by the Center for an Urban Future, New York State saw a dramatic increase in inflation-adjusted NEA funding following the 2008 financial crisis. Between then and the start of the Covid crisis, overall NEA funding for the State steadily declined to just 13% of the size of CRNY’s investment. Among crisis-responsive arts funding initiatives, term-limited employment represents one of the most direct ways to serve artists and their careers.

Employment is a central and limited component of social insurance. The CRNY Artist Employment Program, therefore, was born into these larger contexts. In the end, less than 4% of applications to CRNY’s programs were selected to receive support. The high number of applicants – 2,741 applications for 98 funded collaborations – indicates both the scale of artists’ need for access to a stable income and that many New York artists see employment with community-based organizations as a viable form of support for their work.

Turning to the interview study below, we ask:

- Does a major investment in the financial security of artists’ lives through employment replicate, change, or improve the current inequities faced by disabled workers?

- How does employment affect disabled artists’ social insurance, safety, and wellbeing?

- Did CRNY’s process – from creation to application to deployment of funds – prove to be responsive to disabled artists’ needs?

Part 3: Study Methods

The data for this report come from interviews with 13 artists in the Creatives Rebuild New York Artist Employment Program. Artists were invited to 1-hour, semi-structured interviews on Zoom in late 2022/early 2023 (approximately 6 months after starting in AEP) and again in mid-2024 (near the end of the AEP period). Artists were paid for their labor in the interviews and a review of this report before publication.

This study was designed to give artists agency over the content and form of their participation. Co-optation of disabled people’s experience in research contexts is common. Many artists have been surprised to discover that a casual conversation with a researcher or administrator gets cited as a form of engagement, implicitly legitimating projects they never reviewed or approved. Many Deaf artists have witnessed their expertise being improperly translated from ASL into English. To protect against this, artists were invited to…

- Work with preferred access workers

- Use audio/video for correspondence when reading and writing (emails and documents) posed barriers to access

- Shape the documentation and reporting of their contributions, including options for…

- Video/audio recording, audio transcription, and/or note-taking during interviews,

- Confidentiality, anonymity, and composite characterization during analysis and reporting, and

- Approval of each use of artist-provided data in this report.

Due to the small sample size of this study, all the artists have been anonymized in the sections below. As such, this report uses gender-neutral pronouns throughout.

Artist Sample

According to data gathered during the AEP application and on-boarding, artists were invited to the sample if they…

- Identified as Deaf and/or disabled in their applications materials, or

- Named Deaf- and/or disability-related aspects of their proposed work, and

- Indicated their interest in being involved in research efforts in their application materials.

13 artists matched these criteria, agreed to participate, and provided data that is analyzed in the following sections. One artist needed to leave the study before it was complete and their data are not included in the sample of 13 artists.

Please respect the anonymity of the artists in this sample.

Please do not assume any particular artists are in this sample or attempt to identify artists in the data below.

Please do not contact AEP artists about this report.

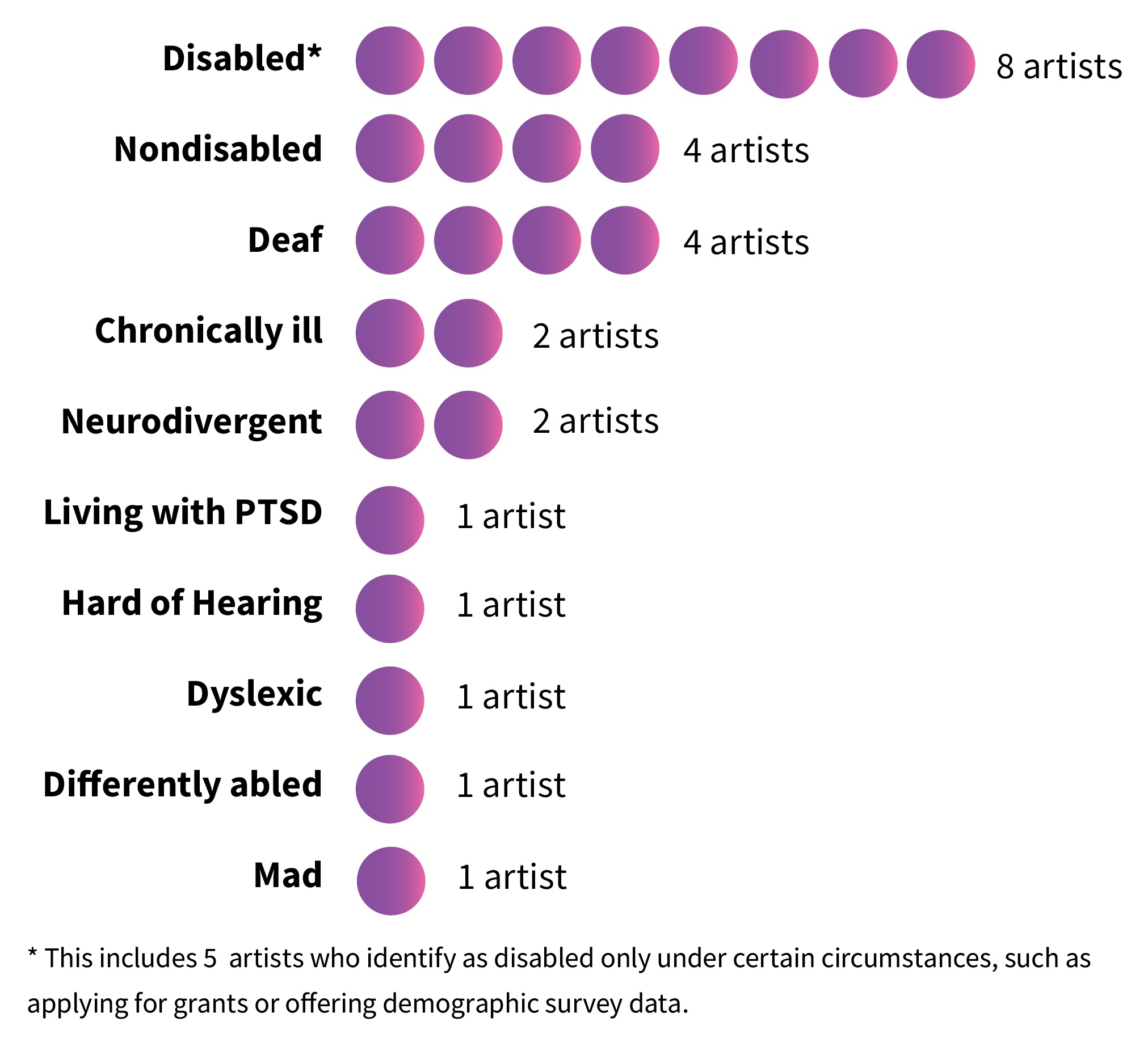

Deaf and Disability Identification

The interviews revealed a range of associations with the identity categories in Deaf and disability communities and culture. The participating artists identify as/with…

Design by Yo-Yo Lin.

These identifiers represent a snapshot in time as the language around disability and artists’ personal reckonings with it are continuously evolving. Many of the artists identified with more than one category in the list above.

Given this range of identifications, there is no single term to accurately describe all the artists involved in this study. In the sections below, you will find various descriptions of artists as Deaf, Hard of Hearing, disabled, chronically ill, neurodivergent, and/or Mad. (The term ‘Mad’ is used by those who challenge language around illness and disorder in mental health frameworks and discourse. It is sometimes considered part of a broader sense of ‘neurodivergence,’ with its own history in the Mad Pride movements in the global north. Its capitalization reflects the efforts to reclaim the term as a form of identity. See Mohammed Abouelleil Rashed, “In Defense of Madness: The Problem of Disability,” The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, vol. 44, no. 2 (March 2019): 150–174.)

Other Demographic Information

The data below are a guide to the sample. One artist requested to be removed from this section. In several of the categories below, artists identified with more than one answer.

Age:

Artists ranged in age from 33 to 65 at the start of the program.

Gender identity:

Cis men (6)

Cis women (4)

Nonbinary (2)

Trans (1)

Sexual Orientation:

Heterosexual/straight (8)

Queer (2)

Bisexual (1)

Pansexual (1)

Race & Ethnicity:

White (7)

Black/African American (4)

Latinx/Hispanic (2)

Location:

5 of the participating artists were based in Western New York, 4 in New York City, 1 on Long Island, 1 in the Greater Capital region, and 1 in the Southern Tier. 2 artists worked across regions and 2 artists also worked across states.

All artists were U.S. citizens.

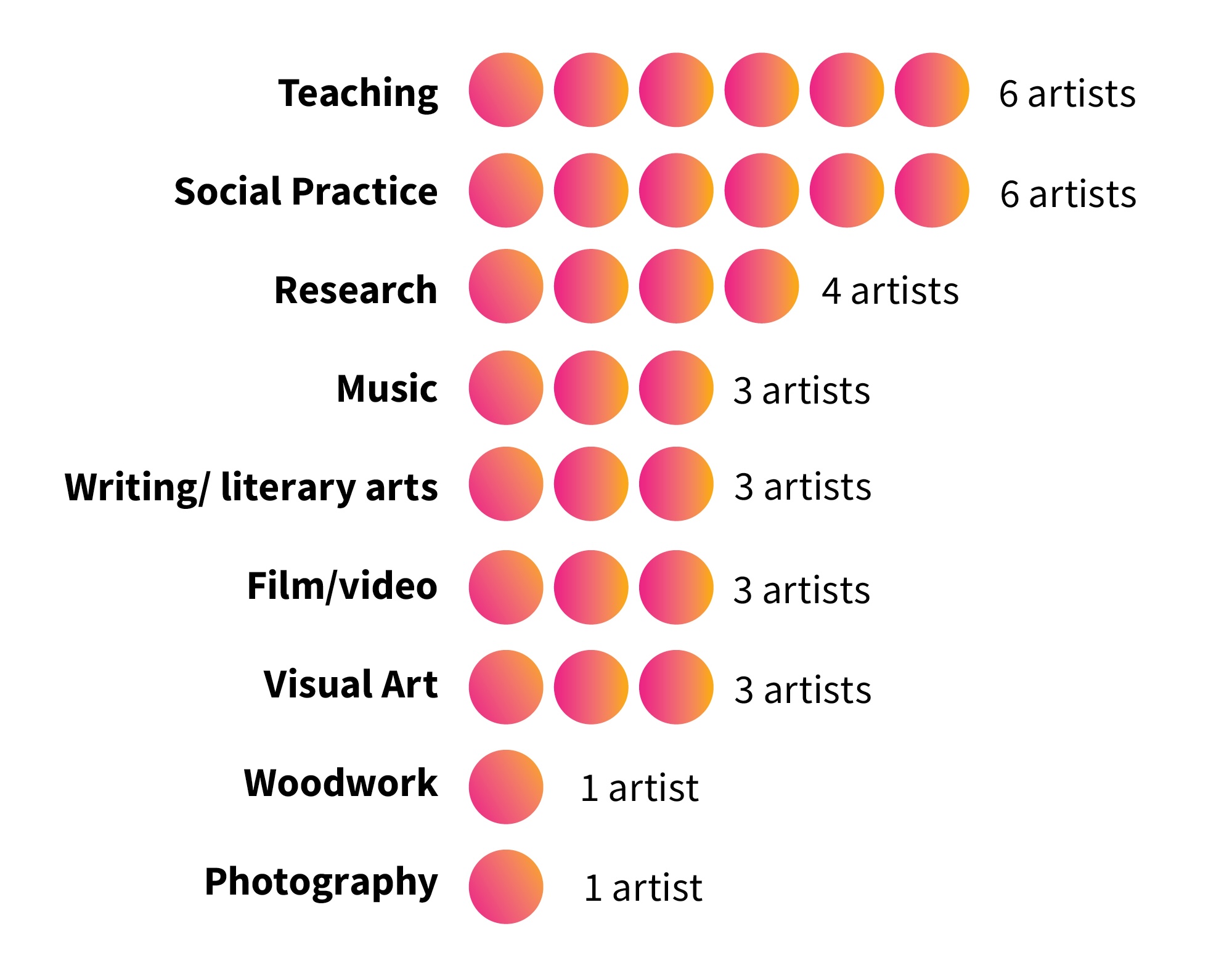

Discipline

The artists identified an expansive and emergent set of disciplinary identifications, often outside of conventional artistic categories. The artists also worked in many disciplines simultaneously, including…

Design by Yo-Yo Lin.

Organizational Collaboration

In the relationship between artists and the community-based organizations they worked with…

- 92% of the artists developed a relationship with their partnering organization/employer well before the emergence of CRNY.

- 2 artists started their collaborations over 20 years ago.

- Most artists describe their organizational connection unfolding across life and professional stages.

Part 4: Results

The CRNY Artist Employment Program generated many stories of success and struggle for artists across New York. These program-wide stories are being documented in the AEP Impact Evaluations conducted by Hester Street Collaborative, Museum Hue, SUNY Empire State, and Urban Institute. Please note that some of this research will not be available until after this report is published and possibly after you read this.

In many cases, the experiences of artists who participated in this study aligned with the broader AEP artist cohort. Artists experienced increased economic stability, professional development, time spent on artistic practice, access to financial services, physical and mental health, and much more. Artists were able to leave unhealthy relationships, care for loved ones, and pay down debts. Similarly, artists struggled to find the best match between their artistic process and the strictures of full-time employment. As noted in the AEP Process Evaluation, “The program has been most successful where artists had a relationship with the organization.” (p. 16)

The sections that follow will draw out successes and challenges that are specific to Deaf, Hard of Hearing, disabled, chronically ill, neurodivergent, and Mad artists or artists working on projects related to these identities, communities, and histories. As you read on, please keep in mind the more widely shared and simultaneous impacts on CRNY’s AEP artists.

Successes

CRNY’s Artist Employment Program created unique positive impacts on Deaf, Hard of Hearing, disabled, chronically ill, neurodivergent, and/or Mad artists, as well as artists working on projects with these communities. These successes imprinted in many ways: on artists as individuals, their artistry, organizational partnerships, and communities.

Innovative forms of Deaf and disability artistry.

The artists in this research cohort created expansive, game-changing, award-winning work that would not be possible without the support of employment. The aesthetic and pedagogical depth is immense: the scale of the work, the documentation and durability of the models that were created in their processes, the audience and community reach, the lasting influences on their collaborating organizations, and more.

- Artistry with accessibility. Some artists worked with access features such as ASL, captioning, and audio description as compositional and artistic tools, part of a larger disability arts movement that is transforming the way art is made, taught, and shown. Some artists also made work specifically from and for the conditions of the ongoing Covid pandemic, the most direct connection to CRNY’s history and mission.

- Community access. Artists made work that could be experienced by disabled communities for free, with adequate support for the compensation of access workers and/or the integration of access features. In some cases, artists made work for and with particular disability communities that are otherwise under-served by the centrality of traditional disciplinary distinctions in arts grantmaking and philanthropy.

Resources for the whole disabled artist.

Some artists reported that they could do their work in ways that match the unique and sometimes inconsistent realities of being disabled. In several cases, this also meant they were able to respond to the way aging affected their disabilities.

- Energy management. One artist, who was working on the presentation of a major new work when they entered the program, was so busy “nothing else could enter [their] brain.” Their salary offered a much-needed respite for the energy-intensive process of debuting work to the public. With inconsistent pay from various jobs, they couldn’t eat out several times per week but they also didn’t have the energy to come back after a full working day to cook for themself. Their paycheck allowed them the financial security to go out to dinner or drinks after showing their work to the world. “It means conserving your energy and not being a zombie or having to function as multiple kinds of artist at once,” they said.

- Covid recovery. One artist’s entry in the program addressed the Covid pandemic’s complex effects on their disabilities. “Covid did a number on my social anxiety,” they said. The program emerged as they were beginning to socialize in new ways. It allowed them to reconnect with an organization that was “a home away from home” in their recovery from the isolating conditions of the early period of the pandemic.

- Healthcare planning. For another artist, the program helped them adjust the realities of becoming a disabled adult. The peace of mind of knowing they didn’t have to hustle with extra gigs and could instead preserve their energy came at an important time in their life. Their employment allowed them to schedule, prepare for, undergo, and recover from a major surgery without foregoing consistent pay. They reported an “emotional agreement” with their colleagues to make this care possible.

- Discernment. The support one artist received was specific to the department they worked within, evolving through personal relationships over years, as the artist’s access needs have changed. “I have really great advocates for me in [this department],” they said. As a result, by the end of the program, they reported being more discerning about what is worth their time, and what is deserving of their expertise and energy.

Supportive working conditions.

With the amount of time and support CRNY provided to both artists and organizations, some artists could imagine long-term, sustainable advancements toward accessible work that too often disappears with a particular leader or employee.

Whereas project-specific arts grantmaking often encourages artists to carry out their proposed work even when they inevitably discover better ways of working, employment allowed artists to transform their plans to respond to their communities’ interests and feedback.

- Disability-centric work cultures. Almost all of the artists who felt supported by their collaborating partners worked with organizations that had cultivated disability-inclusive culture before CRNY’S program emerged. One artist reported that the structures for support they received from their employer came were led by the organization’s staff with disabilities and chronic illnesses. This organization, for example, stressed to all its staff that they should be mindful of others’ working hours and refrain from sending emails late at night. Another artist reported feeling trusted by their collaborators with generous and constructive feedback on their work that came from the organization’s history of developing a unique access-centric mission over time. And another artist discussed the difference it made to have a neurodivergent leader of their organizational partner. With a clear understanding of the artist’s work, this leader was able to make connections to possible collaborations on behalf of the artist and champion their work as part of their leadership responsibilities.

- Project and time management. Some artists were able to use their salary to balance their time and focus on an array of projects. This allowed them to continue their roles in existing non-CRNY-funded projects and created structure for project and time management on their CRNY-funded work. In many cases, artists’ experienced new capacities to slow down and build out the ways they designed, began, and completed their work. Several artists’ full-time employment was focused entirely on their individual artistic practice, affording unprecedented levels of agency and self-direction over their art-making.

- Artistic materials. In one case, an artist who used found materials for their practice, like paint thrown away from schools’ art classes, was able to discover new methods of creation with the resources to buy materials. With a budget for this, they were able to consider the carbon footprints and recyclability of the materials they work with and shop from cause-based retailers to support the work of other artists and organizers. In another case, an artist was able to purchase expensive accessibility software for reading and writing that lowered the barriers to the text-dominated nonprofit art worlds.

- Mentorship and feedback. One artist shared that the Executive Director of their organizational partner helped guide major changes to one of their central projects. “[My ED] gave me a safe space to make mistakes and make better results,” they said. “I stopped feeling bad about change. I stopped being so hard on myself.” In another case, an artist felt like they could show up more as themself despite strained relationships during the program period.

- Career planning. In some cases, artists were also able to develop new professionalized skills and techniques for working within a nonprofit organization, something that can be difficult for artists to access when they often work independently or outside of organizational structures. One shared that the collaboration with their employer built an unusual level of intimacy with the artist’s work that could translate into a strong job reference for future work. Another shared that the program helped their partnering organization form a commitment to presenting their work on a regular basis. One artist who struggled in collaborating with their partner organization was able to imagine what they would need in a new organization they intend to create after the program ended, with specificity about a new entity’s governance and transparency that gleaned from the proximity to their collaborating organization while in the program.

Expansion of the artist role.

Employment offered artists flexibility in how they define and approach their work. In some cases, this went beyond the ‘job’ and expanded how artists show up in the social and cultural lives of their communities.

- Culture bearing. Several artists were able to serve their communities as culture bearers, doing work that is often too broad for project-based arts grantmaking: connecting across communities, generating recognition for work at the intersections of their identities, and planning gatherings that might only come to fruition years down the line. Another artist was able to ramp up their volunteer commitments to nonprofits involved in work related to theirs in order to build new organizational connections. As a result, they were able to use another organization’s space for their art-making and even connected with state lawmakers through the experience.

- Community organizing. Another artist reported being able to identify more as a community organizer. Their salary made it possible to show up across community spaces because they didn’t have to plan their time around sourcing project-specific funding. “I was able to discover and evaluate my role in movement work,” they said. “I was able to really think about what work is for me to do, what is suited to me and my experience, and how I can help work that can only be led by others.”

- Caregiving. Several artists were able to use the flexibility afforded by their employment to take care of family members.

Financial wellbeing.

One artist, prompted for their successes in the program, answered: “The money, simply.” They were able to complete “a tremendous amount of projects” without the “extra stressors” associated with finding, applying to-, managing, and completing grants. “The money made it possible for me to function as a human being […], to give all of myself to [my] process,” another artist said. “I can’t overstate the importance of not having to worry.”

- Paycheck stability. In interview after interview, artists reported that they would have continued making their work with or without the CRNY funding. But with it, they were able to move more freely and with less stress. One artist described “what it does to my mental health to know I’ve paid rent, credit card, utilities. I see that come out of my checking account and that’s okay because in 2 weeks I’m going to have another paycheck.” After advocating for something they needed as a disabled artist, they reported “not being afraid that the opportunity will be taken away.”

- Savings. Artists were able to save money, something that was previously difficult for many. One artist reported that the program helped them get “much closer” to reaching the savings they need to retire in the next few years. The consistency and reliability of their paycheck allowed them to plan for longer-term financial stability. The program also helped them save indirectly. For example, one artist reported being able to pay for much-needed repairs on their house.

- Financial services. Another artist reported an increase in access to financial services, such as financing for home-buying that is often limited for those without W2 employment. They were able to increase their credit score, reducing interest rates on debts that will impact their financial future long after the program.

- Supplemental compensation. In several cases, employment allowed artists to access additional compensation for their own artistic practice, increasing their overall pay.

- Secondary wage effects. Several artists reported being able to pay collaborators a living wage with the funding they received from the program, creating effects for a broader network of artists across New York.

Challenges

The challenges faced by the artists in this study help us understand patterns of experience that are often missed in generalized programmatic evaluations.

Discrimination and exploitation

One artist experienced discrimination for needing more time for their work than their employer expected of them. They reported that anti-discrimination laws did not help. When they tried to advocate for themself, their employer sought to “quietly fire” them. This had a strong impact on their entire life. They were so overworked by their employer that they could barely do their laundry. As a result, they relied more heavily on their partner to keep up with tasks that are crucial for- but not directly related to their work. It even changed the focus and kind of work they did, diverging from the projects they had planned for given previous agreements.

When one Deaf artist sought professional development support, they were given candid advice about the realities of accessing resources in the art world. They were told “people just don’t want to deal with ASL interpreters” and that they should plan to bring their own interpreters to meetings. Perhaps well-intentioned candor when framed as “professional development,” this advice is discriminatory and strengthens the audist status quo Deaf artists experience on a daily basis. Recommending that an artist pay for their own access out of pocket is one clear example of the financial and emotional burdens Deaf artists face.

Cohort and program parity.

In general, artists who reported overall success in their employment worked with large and long-standing organizations, suggesting cohort-wide inequities for smaller and newer organizations.

Several artists identified that the program’s $65,000 salary was not equal among the 300 artists in the program. As one artist shared, “It’s not really a $65,000 salary when you factor in ongoing healthcare expenses and unaffordable healthcare coverage.” (This is also noted in the AEP Process Evaluation. While CRNY’s living wage for artists was matched to the statewide median income, “median income varies dramatically from region to region. Pay parity became an issue in the several cases in which AEP artists made a higher salary than other staff at the participating organization. This was further complicated by the perception that artists had fewer responsibilities because they were paid to do their artistic practice alongside organizational work. The disparity between participating artist salaries and median salary in regions where cost of living is lower than others may also mean that many organizations will not be able to sustain the salary after the program’s sunset, resulting in unemployment.” Also: “Out of pocket healthcare costs—for things like deductibles, specialist care, and premiums for other family members—ran especially high for those with chronic care needs, and network coverage was lacking in rural areas and for those seeking mental health care.” pp. 11 – 12) A 2020 study from the National Disability Institute found that disabled families require an average of 28% more income than nondisabled households – $17,690 each year – to experience the same standard of living. When the cost of an inaccessible world falls on disabled people and their families, standardized pay rates mean disabled workers earn less.

For another artist, the centrality of reading and writing created difficulties in accessing various employment supports. The brevity in some paperwork, for example, made it hard to understand the context and applications for various forms. Using their new health insurance plan involved waiting for emails and updates from the plan provider. “It can take a whole day,” they said, “just to make a [doctor’s] appointment.”

For artists who had little or no obligations to the administration or output of their collaborating organizations, the Artist Employment Program was more accurately a guaranteed adequate income, an increase of roughly 400% compared to the level of support offered through CRNY’s Guaranteed Income for Artists Program for essentially the same requirements of the artists. (This comparison is an estimate because the AEP salary is subject to tax withholdings and other paycheck deductions that are specific to each artist, whereas the Guaranteed Income for Artists funds met the IRS gift definition and therefore was non-taxed income.)

Inconsistent access design.

CRNY was made up of a small team managing several large-scale initiatives. These unique circumstances made it difficult to offer consistent and trustworthy access features across all its offerings to artists, organizational partners, and a broader public. As such, the organization relied on an array of collaborations for the implementation and administration of its work, serving different audiences at different points in time.

As a result, it was often challenging to centralize and disseminate the information about access for consistent access design of meetings, workshops, and events. In some cases, inconsistencies in access emerged because the staff of a collaborating organization was unfamiliar with how to schedule and adequately prepare access workers for meetings or events. When one Deaf artist asked an organization for information about the ASL interpreters hired for an upcoming event, they were told not to worry about it because they had already hired these workers. “We’re a huge part of the process of the service provision,” the artist said. “I may need to help them prepare or ask for someone different.” The logistical details – down to where an interpreter stands or how a Zoom meeting is configured – is where good access design is made.

At one event, an interpreter hadn’t eaten breakfast or lunch before beginning their work. They tried to eat while interpreting, which compromised the level of access for Deaf attendees. When one attendee invited the interpreter to take a break to focus on eating, they were able to use captioning as a temporary form of access. However, ASL is the cultural and linguistic lifeblood of Deaf community and captioning is not a sufficient replacement for ASL.

“It takes a specific skill set and kind of interpreter to be able to voice for me,” said one Deaf artist. When they knew and trusted their interpreters, they didn’t have to spend extra energy adapting to- or compensating for an unfamiliar or incompetent access worker. This artist recalled a day full of meetings, including a difficult one, when they had access to their preferred interpreters: “I didn’t have to worry about the content and the interpreter,” they said. “I was on a roll.”

Collaboration structure.

The Artist Employment Program was designed to give a high degree of agency to artists and their collaborating organizations. This meant that the specifications about artists’ employment were highly dependent on the structures and stability of the organizations and relationships between artists and organizations. This overall autonomy often created uncertainties and conflict.

One artist described the fast-paced nature of their organizational partner that comes with their mutual aid work. “It leaves out those of us who can’t do 10 things at once,” they said. This generated some hard conversations with the organization’s leadership. For the artist, the employment program offered some stability and time to slow down their process. But the organization kept with the pace of their existing work, so much so that leadership didn’t give the design of the collaboration their fullest attention until after they were selected for the program. The formalization of the collaboration, including long-term budgeting that was unusual for an under-resourced community-responsive organization, created fear among the leadership and added tension to their relationship with the artist.

One artist reported on a change in leadership during the program period, from a neurodivergent director to a neurotypical one. While the new leader was still “extremely supportive” of their work, they said, “the relationship is different” and there was a need to build a shared framework of understanding that previously undergirded their collaboration.

One artist was asked to act as a consultant on a large-scale architecture project around disability access at their partnering organization. In this case, the artist was able to advocate to bring other experts into the conversations.

Missing political context.

Artists felt disconnected from CRNY’s policy and advocacy work. “In spite of the fact that I’ve been inside the program for 2 years,” one artist shared in an interview at the end of the program, “I still am not sure that I understand exactly what it was all about.” They spoke about the effects on their own life and the work of their collaborating organization (“incredibly positive all the way around”), but it was hard for them to make sense of the larger intervention CRNY’s program was making throughout the state.

Another artist shared disabled rage at experiencing the eugenics consistent with U.S. public life growing increasingly apathetic to Covid over the course of the program period. They often found themself in the minority in providing remote/hybrid event options and asking about masking and testing guidelines for in-person events which began to disappear from event information. A new status quo mindset seemed eager to cordon off Covid as a matter of no concern. CRNY, as a pandemic relief initiative, should have been more attuned to the immunocompromised and disabled artists who were most affected by the ongoing pandemic.

Program cliff.

Several artists explained how the financial stress and precarity the Artist Employment Program was designed to alleviate came crashing back in when it ended. (This mirrors general trends for the ending of Covid pandemic relief programs. A report from the New York State Comptroller’s Office from May 2024, for example, shows that child poverty decreased 51% as a result of expanded benefits under the Child Tax Credit, enhanced food benefits (SNAP), emergency rental assistance, among others. When these programs ended, the rate of child poverty more than doubled, surpassing its pre-pandemic levels.) The time when artists needed to prepare for the program’s end also often coincided with concluding exhibits, performances, and workshops that were the culmination of their AEP-funded work. As a result, in the spring and early summer of 2024, artists were sometimes scrambling to both plan for their next sources of income while completing 2 years’ worth of work for public display.

One artist’s plan for a disability-centric project needed to be tabled when work with nondisabled community groups took longer than anticipated. The irregularities of project and time management in collaborative artistic work and the rigid cutoff of funding meant that some disability-focused work became part of the program’s cliff.

The Importance of Health Insurance

Health insurance coverage that meets the needs of disabled artists is one of the most crucial aspects of an employment program’s success – and one of the most complex. Healthcare emerged in many ways in the artist interviews, noted in the results above. However, disability-specific research in this area is urgently needed.

For disabled, chronically ill, and immunocompromised artists, employment can reduce overall access to resources, with profound implications for their lives and work. Urban Institute’s report “Empowering Artists through Employment: Impacts of the Creatives Rebuild New York Artist Employment Program” released in November 2024 collects important testimony from artists about the CRNY health insurance options:

“[Artists] noted significant and, in some cases, troubling challenges [with health insurance], particularly for artists with disabilities and serious health concerns. One artist who was employed by and received benefits directly from a partner organization shared that they delayed medical treatment because of the cost of deductibles, ended up needing surgery because of the delay, couldn’t cover the medical bills, and saw their credit score negatively impacted. Another shared that the organization ‘messed up’ their coverage and had to delay a medical procedure for over a year. Some artists employed by Tribeworks recounted experiences with lack of coverage and disappointment with how the company helped them navigate. For instance, one shared, “A lot of treatments and prescriptions weren’t covered. They apologized, washed their hands, didn’t really help…. It was a really disappointing experience.” Another shared that their insurer option was not ‘affordable’ in terms of deductibles and copays offered and that the prescription drugs they needed were not covered. The artist said, ‘I didn’t know until way after that I could’ve stayed on Medicaid for longer or navigated Marketplace options.’” (P. 33)

These experiences indicate how the design of an employment program can maintain and exacerbate the effects of an ableist health system. They reveal the ongoing precarities for disabled artists as cultural institutions falsely claim that the Covid pandemic is over. They also demonstrate how the U.S. healthcare market limits the options available to arts organizations to adequately address what disabled artists need.

Within the complexity of the issues, we will note 2 considerations for artist employment programs:

- Many disabled artists need employer-sponsored health insurance. They need coverage that eliminates or minimizes the costs of premiums, deductibles, co-pays, and out-of-pocket expenses. In some cases, it may be possible to provide this kind of care through Health Reimbursement Arrangements with employer contributions at the amount of an insurance plan’s out-of-pocket maximum. This is an abbreviated example of a way employers might address artists’ often-prohibitive costs.

- However, employer-sponsored health insurance will not work for all disabled artists. Significant medical expenses, such as the cost of a new powerchair or a costly live-saving medication, are rarely covered by any employer-sponsored plan. For these artists, it is critical that they do not lose access to public healthcare benefits like Medicaid that are some of the only plans that adequately cover what disabled artists need to live. The protection of public benefits eligibility is the subject of other research by Kevin Gotkin in the context of CRNY’s Guaranteed Income for Artists Program. For more, see “Crip Coin: Disability, Public Benefits, and Guaranteed/Basic Income.”

Part 5: Recommendations

What do we learn from these experiences of the Deaf, Hard of Hearing, disabled, chronically ill, neurodivergent, and/or Mad artists in the CRNY Artist Employment Program cohort? How can we synthesize these lessons to craft better artist employment programs in the future? The recommendations below reflect on the data above and offer some recommendations artists made during our interviews at the conclusion of the program.

Please note: Some important recommendations about employment are published in separate reports. It is recommended to read “Crip Coin: Disability, Public Benefits, and Basic/Guaranteed Income” and “Plain Language for Arts and Culture” along with the following section.

Design a selection process with and for Deaf and disabled artists.

The ways artists learn about, apply to, and are or are not selected for an employment program builds the foundation. Several aspects of CRNY’s work were successful in this area and should be replicated:

- Artist leadership. Deaf and disabled artists’ direction over program design and cohort selection is a crucial dimension of meaningful access and the overall impacts on artists’ work and lives. It is especially helpful to engage organizers who are engaged in cross-institutional work to advance the field of Deaf and disability arts.

- Access-oriented outreach. Paying Deaf and disabled artists to spread the word about the program application is essential. It is important to plan for many forms of communication beyond email and social media, including word-of-mouth and promotional programming with disability organizations.

Two of the most promising aspects of the CRNY program – the expansion of disability-centric workplaces/work cultures and employment as an interruption of cycles of disability financial instability – must begin with how organizations are selected.

- Disability-responsive pacing. It takes time to make new relationships with Deaf and disabled artists. It also takes time to understand and go beyond the reach of specific professionalized networks. Artists and organizers do their best work when they feel they have more than enough time. Paychecks and savings for disabled and chronically ill artists can become tantamount to resilience and agency when the basis for collaborations with organizations is built over time.

- Organizational audits. Because of the challenges to workplace accessibility discussed throughout this report, disabled workers are often saddled with the work of educating colleagues, advocating for themselves, and implementing necessary accommodations. Early assessments of an organization’s capacity to meet the access needs of its employees could go a long way in identifying and shaping successful collaborations that allow artists to do their best work. This may include the review of:

- Covid safety measures.

- Remote work protocols.

- Physical and spatial access where artists will work,

- Physical and spatial access where programs/events/workshops will take place,

- Employee on-boarding processes.

Plan for reliable and high-quality language access.

Equitable access to all aspects of a program’s offerings is a civil right. This means understanding and being responsive to the access features of the artists, communities, and organizations being served by an artist employment program. Programs with broad scopes and scales can end up using many different communication and event partners, which can pose challenges to the consistency and therefore reliability of necessary access features.

There is no single set of access offerings that will meet all Deaf and disabled artists’ access needs. Access design is an artful dimension of organizing and program administration. It requires time and focus to learn what various community members need and to iterate better ways to meet these access needs. This often means transforming the amount of time, adaptability, and sophistication of event and program planning processes. When access design is built with artists, it makes a major difference.

To ensure meaningful access of all programmatic offerings:

- Use participants’ preferred access workers. Gather their contact information and schedule with these providers consistently.

- Deaf participants’ preferred ASL interpreters (including Certified Deaf Interpreting teams) and Hard of Hearing or neurodivergent participants’ preferred captioners should be adequately prepared for each engagement with the context and anticipated unfamiliar vocabulary for an event ideally one week in advance.

- Access workers should be compensated for the time to prepare, especially when they may need to study new forms of language they don’t already know such as religious vocabulary.

- For in-person gatherings, some access workers need to work closely with specific participants, like Designated Interpreters who move with a Deaf participant to interpret conversations apart from an audience-facing interpreter for a presentation.

- Some access workers also need to plan for masking requirements, such as using a clear mask to offer lip-reading access.

- Require a comprehensive access training protocol. This should be built into any contracts with partners involved in coordinating meetings and/or events. This training should explain the elements of access design, direct collaborators to information about the access needs of anticipated participants, and how to approach design for a public audience. Materials relating to ASL should be led and designed by Deaf people.

- Designate an access coordinator. Provide the contact information for the specific person who will coordinate access. This should be included in all promotional materials and communications with meeting/event participants. This is greatly enhanced by having the same coordinator for all events, especially having an access coordinator at the central funding/administering organization who can work on annual/long-term access planning. When working on Deaf-specific access plans, this coordinator should be Deaf.

- Offer real-time language interpretation for non-English speakers. Adequate preparation of the interpreters is essential for equitable access. Slow pacing and plain language helps interpreters do their best work, especially when working on English materials that may not have direct references in other languages.

- Use plain language. When addressing a general audience, plain language is the best way to make sure that the largest number of people can understand written and spoken materials. In some cases, it is necessary to translate an existing document into plain language before it is widely publicized.

- Go beyond email. Some artists need communication via text messages or phone calls.

- Plan for learning curves and sustainability. Access design and coordination is a skill that needs to be developed over time and maintained. This requires the support of specific staff members and plans for transferring their expertise to new staff when they leave an organization.

Offer clear and detailed guidance on the structure of employment.

Protecting the autonomy of artists and their employers can be enhanced with specificity about how the collaboration is structured.

- Offer salary choices. Artists who use means-tested public benefit programs may experience major uncertainties about their access to resources with a new salary. Given a choice, some artists may elect a lower salary that would provide them with an overall increase in access to resources.

- Provide feasible distinctions between artist work and artist practice. When employment is designed to support an artist’s individual practice in addition to their work with an organization, all collaborators need specific methods for understanding the difference. These might include:

- Scheduled work weeks, including the working hours of artists on given days,

- Scheduled work months, then including the working hours within the work weeks,

- Schedule work seasons (especially helpful for seasonal projects), then including the working hours within the work weeks

- Regular meeting and/or co-working times,

- Task- and project-based schedules with clear measures for completion.

- Protect artists from becoming consultants. Cultural institutions are increasingly seeking disability engagement for capital and infrastructure projects. Disabled artists are not always technical experts in the design of the built environment and their conversations about access can be co-opted to fill gaps in the services of architects and designers. While some disabled artists are finding new and important kinds of income in advising access-related projects, others feel obligated to help with work they didn’t choose to work on. Unless it is specifically part of the collaboration, the employment of disabled artists should not be treated as in-house accessibility expertise.

- Be mindful of the effects of professionalization. Some artists do not work in communities where it is possible to attend a meeting or event in the middle of the workday. Reputational networks can amount to resource-hoarding when work is made available only to a small group of people. In some cases, the invisible labor an artist puts in to match an unfamiliar workplace standard can be taken as evidence that they are not disabled. Invite artists and organizations to name the kinds of etiquette that often go unspoken in professional settings.

- Pace deliverables strategically. Program design should limit the overlap of culminating work with the preparation for their next sources of income. Some artists might, for example, present work in the middle of their employment period and conduct evaluation or review of the work in the concluding part of the employment period.

- Limit the imbalance of power – and its perception. Some employers may have existing personal or professional relationships with the funding/administrating organization of an employment program and/or its staff. If these organizations are selected to be a part of the program, it can leave the artist-workers unclear about “who holds all the cards,” as one artist explained in an interview. They “felt like a failure” when they needed to reach out to intermediaries for support on workplace conflict. Bright-line transparency about the roles and objectives for each area/organization/person involved in the employment structure could help lower the barriers to addressing harmful employer behavior. Funding organizations should also address artists’ concerns about the broader effects on their career and professional connections if they seek help with harmful employer behavior.

- Plan for staffing shifts. Employment program guidelines and the documentation of collaboration they require can form an essential basis of understanding when an organization’s staff and/or leadership changes during the employment program period. This helps protect artists’ time, agency, and integrity of their proposed work.

Provide thorough intermediary support for artists and organizations.

Federal anti-discrimination laws like the Americans with Disabilities Act and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 require that employers create the conditions for an employee to successfully perform their job. These laws, however, don’t apply to employers with fewer than 15 employees, which is how many nonprofit arts organizations operate. Similarly, the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (FMLA) only applies to employers with 50 or more employees and doesn’t protect workers who have been employed for fewer than 20 workweeks.

On the state level, New York State’s Human Rights Law prohibits “discriminatory action because of a history of disability or because of a perception of disability” for all employers. However, artists’ use and trust of these protections is often made difficult by several factors, including:

- Required medical documentation that obligates an employee to furnish intimate health information to their employer. The employer is required to keep such information confidential, but there is little protection for this or enforcement of penalties if the employer fails to maintain confidentiality.

- Lack of interpretive guidance. How an organization understands definitions like ‘essential job functions’ of the employee or ‘undue hardships’ on the employer can diverge significantly from how a disabled or chronically ill artist might understand them. Without strong support for ways to close this distance, the employer often retains its power to wear down an employee. (See Jeanette Cox’s article “The ‘Essential Functions’ Hurdle to Disability Justice” in Ohio State Law Journal (vol. 84:3, 2023) on how courts are increasingly weakening the ADA by superficially understanding the definition of ‘essential functions’ a worker must perform with or without accommodations as a condition of a ‘qualified individual.’ The law’s requirement of ‘essential functions’ was meant to expand the scope of protection by intervening against employers’ perception that disability is in itself a disqualifying feature for employment. The misperception that the term ‘qualified individual’ is about who the law protects – and now how disabled workers might already be qualified to work – is indicative of the ableist status quo put forth by the very courts who are meant to protect the integrity of disability legislation.)

Additionally, disability-specific workforce development initiatives like Competitive Integrated Employment are rare in the arts and culture sector.

Therefore, the role of the funding/coordinating organization and staff for an employment program can make a major difference on the experiences of Deaf and disabled artists. Intermediary artist support might include:

- Mediation and facilitation. It is essential to prepare detailed plans for handling conflicts that arise between artists and their employers. Hiring skilled mediators with anti-carceral methods and values is an important part of this. It’s also important to attend to the changing needs and recovery periods of these facilitators.